Emory ichnologist Anthony Martin wants to shake up your view of dinosaurs by letting you follow them in their tracks. (Warning: Watch where you step.)

Martin is on a mission to bring ichnology to the masses. Long overshadowed by the bone specialists of paleontology, paleoichnologists focus on the fossils of tracks, nests, burrows, dung and other traces of life.

Martin’s new book, “Dinosaurs Without Bones: Dinosaur Lives Revealed by Their Trace Fossils” is published by Pegasus Books. In a review, Publisher’s Weekly says Martin’s writing “bubbles over with the joy of scientific discovery as he shares his natural enthusiasm for the blend of sleuthing and imagination that he brings to the field of ichnology.”

Martin also drew all of the illustrations for the book, and took most of the photos.

eScienceCommons interviewed the author in his office in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences.

eScienceCommons: Your previous five books have been geared more towards academics. Why did you decide to write this one for a general audience?

Tony Martin: One of my goals is to help turn the term “ichnology” into a household word. And I want to help people see dinosaurs in a new way: Not just as skeletons in a museum, but with muscles and flesh, moving and making traces.

eSC: What sort of readers do you think will enjoy this book?

TM: Anyone who loves dinosaurs. But also people who love detective stories, which often involve the scientific method. Sherlock Holmes, who was a nerd long before it was hip, is making a comeback as a TV series. A lot of people enjoy watching him solve problems by making careful observations, and then forming hypotheses on the basis of those observations.

I’m writing about mysteries that, in some cases, go back more than 100 million years. Dinosaurs left behind many observable clues about what they did while they were alive.

You see a deserted plain. Here's what an ichnologist sees. Drawing by Tony Martin.

eSC: You open the book with a thrilling scene, of two big, male Triceratops charging across a floodplain, creating havoc among a group of feathered theropods and a flock of toothed birds and pterosaurs. It’s a bit like Jurassic Park without the humans.

TM: Almost everything that happens in that opening scenario is based on real evidence. It’s creative non-fiction, describing behaviors as they may have happened, based on trace-fossil records. There is a lot of action in the book. It’s not just a mystery – it’s also a thriller.

eSC: I love it that one of your favorite trace fossils is of a dinosaur butt.

TM: It is rare to see a dinosaur-resting trace. One of the best examples is from a small theropod, discovered in Utah. It’s intriguing to me to think of a dinosaur sitting down and leaving an impression. Why did it sit down? To digest a big meal? To survey a scene? Dinosaurs don’t always have to be running, eating machines.

eSC: You also write about dinosaurs belching, breaking wind, peeing, pooping and even puking. You seem almost shameless in your quest to appeal to the masses.

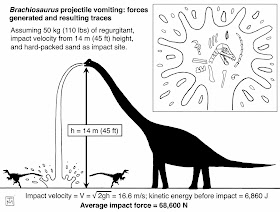

TM: If there is anything that will get me on The Colbert Report, it’s my diagram of a Brachiosaurus projectile vomiting (see above), including the estimated impact velocity of the stream and the associated crater. I checked with (Emory physicist) Jed Brody to make sure I got the physics right. It’s a fantasy trace fossil – no one has found an undoubted trace fossil of dinosaur vomit yet – but that doesn’t mean they aren’t out there.

eSC: And, of course, you have included dinosaur violence and sex.

TM: Trace fossils of fighting can tell you a lot about dinosaur behavior. For instance, we have evidence of a Tyrannosaurus taking a chunk out of the tail of an Edmontosaurus, which survived the damage. The trace fossil marks of the teeth row on the skeleton are more than a foot across, which narrows down the list of perpetrators to a tyrannosaur closely related to Tyrannosaurus rex, or T. rex itself.

Part of my inspiration for writing about dinosaur sex comes from a section in the book “My Beloved Brontosaurus,” by Brian Switek. He described the spikes on the tails of stegosaurs, and pondered how the males might have gotten past those.

I thought I’d take that idea a step further and imagine what kind of trace fossils dinosaurs might have made while mating.

"A cassowary really looks like something out of Jurassic Park," says Martin. Photo by Paul IJsendoorn/Wikipedia Commons.

eSC: Your book chapters have some dynamite opening sentences. One of my favorites is, “The large theropod tracks were fresh, and so was its scat.”

TM: We can observe dinosaur behavior by studying and tracking the traces of birds, which are living theropods. Those particular tracks were from a cassowary encounter I had during a field trip with Emory students in Queensland, Australia.

The sunlight was coming across this giant bird as it was crossing a stream. It was an amazing sight. Cassowaries can grow to more than six-feet tall. They’re among the tallest, heaviest birds alive. They are covered with black feathers, and their head is topped with a tall, bladed crest that looks as if it can saw through flesh. A cassowary really looks like something out of Jurassic Park.

eSC: How long did it take you to write this book?

TM: In terms of experience, the book took 30 years of work in ichnology and geology. It took a while for me to develop the right combination of field experience, knowledge and writing ability to put it all together into something a reader would enjoy.

The actual writing of the book took just a little more than a year. It really flowed out of me. It was fun to write because I got to blend my scientific expertise with pop culture and other human-interest topics to tell a story that uses ichnology as a central theme.

Here in the United States we like to bemoan how we have a scientifically illiterate public, but people are interested in good science stories. I would encourage more scientists to think about writing in ways that are approachable to general audiences.

eSC: Who are your favorite science writers who appeal to general audiences?

TM: There are so many good science writers now. To name just a few that I enjoy: David Quammen, Virginia Hughes, Ed Yong, Brian Switek, Carl Zimmer, Virginia Morell and Annalee Newitz.

Related:

Dinosaur burrows yield clues to climate change

Polar dinosaur tracks open new trail to past

Lake-bed trails tell ancient fish story

Tell-tale toes point to fossilized bird tracks