Wednesday, May 29, 2013

A healthy business is in his cards

Eddie Kovel just graduated from Emory with the unusual combination of a business major and a predictive health minor, fashioned with the support of the Center for the Study of Human Health. One of the fastest growing sectors in the economy, the human health field is creating new opportunities in medicine, business, law, public policy, the arts and elsewhere.

“There’s definitely an emerging need for business-minded health professionals and health-minded business professionals,” Kovel says.

Kovel has developed a card game called “Playout” which aims to motivate people to exercise. He’s now working to spread the word about the product, and its philosophy of having fun while getting fit.

Related:

Predictive health: A call to reinvent medicine

Friday, May 24, 2013

A medical exhibit that won't put you to sleep

"Medical Treasures at Emory" is an exhibit of historical artifacts that serve as reminders of the days when doctors had a rudimentary understanding of human anatomy, performed surgery without antiseptic and used primitive forms of anesthesia for operations and dental work.

The above video gives a peek at some of the objects on display through October at the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library. Notable artifacts include one of the earliest stethoscopes from the 19th century, and a kit of Civil War surgeon's instruments, primarily used for amputation.

Among the historical books on display are volumes about Civil War field surgery practices, an 1881 book that incorporates early medical photography to show the ravages of syphilis, a copy of "Notes on Nursing: What It is, and What It Is Not" (1865) by Florence Nightingale, and an 1849 obstetrics book by Charles D. Meigs, an obstetrician who opposed anesthesia and the introduction of sanitary practices during childbirth on the theory that "doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman's hands are clean."

Also on display is a rare copy of "One the Workings of the Human Body," or "de Humani corporis fabrica," a 1543 book containing the first accurate representations of human anatomy.

Read more about the exhibit.

Related:

The rare book that changed medicine

Objects of our afflictions

The above video gives a peek at some of the objects on display through October at the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library. Notable artifacts include one of the earliest stethoscopes from the 19th century, and a kit of Civil War surgeon's instruments, primarily used for amputation.

Among the historical books on display are volumes about Civil War field surgery practices, an 1881 book that incorporates early medical photography to show the ravages of syphilis, a copy of "Notes on Nursing: What It is, and What It Is Not" (1865) by Florence Nightingale, and an 1849 obstetrics book by Charles D. Meigs, an obstetrician who opposed anesthesia and the introduction of sanitary practices during childbirth on the theory that "doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman's hands are clean."

Also on display is a rare copy of "One the Workings of the Human Body," or "de Humani corporis fabrica," a 1543 book containing the first accurate representations of human anatomy.

Read more about the exhibit.

Related:

The rare book that changed medicine

Objects of our afflictions

Monday, May 20, 2013

Parasitic wasps use calcium pump to block fruit-fly immunity

A parasitic wasp on the prowl for fruit fly larva to inject with her eggs.

By Carol Clark

Parasitic wasps switch off the immune systems of fruit flies by draining calcium from the flies’ blood cells, a finding that offers new insight into how pathogens break through a host’s defenses.

“We believe that we have discovered an important component of cellular immunity, one that parasites have learned to take advantage of,” says Emory University biologist Todd Schlenke, whose lab led the research.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the results, showing how a wasp version of a conserved protein called SERCA, which normally functions to pump calcium from the cell cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum, can block a host’s cellular immune response.

“Before our study, there were hints that calcium signaling was important for blood cell activation following infection, but the fact that a parasite actively suppresses this signaling shows how important it is, Schlenke says. He adds that the insects can serve as a model for more complex human immune systems.

“It’s incredible the way the wasps use a protein in their venom to control the flies at a molecular level,” says Nathan Mortimer, a post-doctoral fellow in the Schlenke lab who conducted the experiments. “Instead of killing the fly immune cells, the wasps actually take over blood-cell signaling, manipulating the host’s cellular behavior from the bottom up.”

The research team also included Emory biologist Balint Kacsoh; Jeremy Goecks and James Taylor, from Emory’s departments of biology and mathematics and computer science; and James Mobley and Gregory Bowersock of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

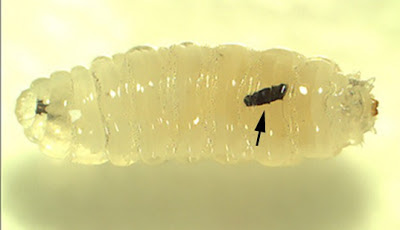

Fruit fly wins: A wasp egg has turned black and died (see arrow) inside the larva of a fruit fly that has mounted a successful immune response.

Fruit flies and the tiny wasps that parasitize them have co-evolved complex strategies of attack and defense. The wasps inject their eggs into the body cavities of fruit fly larvae, along with venom that aims to suppress the flies’ cellular immunity. If the flies fail to kill the wasp egg, a wasp larva hatches inside the fruit fly larva and begins to eat its host from the inside out.

“The wasp larvae have these sharp appendages, like the fingers of Edward Scissorhands, that they use to stick into the fly tissue and start eating,” Mortimer says. “It’s a brutal process.”

In previous research, the Schlenke lab has shown how fruit flies sometimes use alcohol in rotting fruit as a drug to kill the wasps.

In the current study, the researchers focused on the molecular attack strategies of the wasps. After sequencing the transcriptome of the newly described wasp species Ganaspis sp.1, they took a proteomic approach to identify peptide sequences out of the wasp’s venom gland, which they could then link back to full-length transcript sequences.

“We found that the venom of Ganaspis sp.1 is a toxic cocktail of 170 different proteins,” Schlenke says, “but the most prominent component was the SERCA calcium pump protein. That really surprised us.”

Wasps win: Arrows point to wasp larvae that have successfully blocked the fruit-fly immune response and are eating the tissue of the fruit fly.

Calcium pumps are found in the membranes of every living cell of every animal, and are needed to maintain ionic homeostasis and cellular stability. One type of pump moves calcium ions out of the endoplasmic reticulum and into the cytoplasm where they transmit signals that activate other proteins. The SERCA calcium pump operates in the opposite direction, sucking calcium ions out of the cytoplasm and back into storage.

“We wondered why the wasps would inject the flies with a protein that the flies already have, and that every cell needs to function,” Schlenke says. “How could that be an infection strategy?”

The researchers knew of studies suggesting that a calcium burst in cytoplasm is associated with the activation of human blood cells. They wondered if something similar was happening with the flies.

Mortimer conducted experiments on a transgenic fly strain with cells that fluoresce in the presence of calcium. He found that the fly blood cells release a burst of calcium into their cytoplasm, and that this activates the blood cells to start homing in on the wasp eggs. Genetically increasing or decreasing blood-cell calcium levels makes the flies more or less resistant to the parasite infection.

“The wasp venom prevents this calcium burst, and it’s like the fly blood cells don’t realize they’re supposed to be responding to infection,” Mortimer says. “The venom essentially sucks the calcium out of the fly’s blood cells.”

The experiments showed that the wasp venom is specifically targeted to the fly blood cells, and has no effect on other cells.

An unresolved question is how a SERCA protein, which is hydrophobic and normally resides in an oily membrane, moves out of a wasp venom cell and makes its way into a fly blood cell.

“We have no idea how it works,” Schlenke says, “but somehow this calcium pump moves through all these environments and finds its way into its target cells.”

The researchers hypothesize that virus-like particles in the wasp’s venom may be involved. “If they aren’t really viruses, they seem to be some virus-like thing that the wasp has invented,” Schlenke says. “It’s pure speculation, but we think maybe the wasps use these particles as delivery vehicles for the calcium pumps.”

Previous research has established that fruit fly immune signaling pathways have homologues in humans, making fruit flies a valuable model for learning about human immunity. That work led to the award of the 2011 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine to Jules Hoffmann, a fruit fly immunologist.

Studying the wasp-fly battle for survival at the molecular level provides a powerful new tool for unlocking more secrets of immunity that could apply to human health, Mortimer says.

“I’m also interested in using the flies to understand more about the immune systems of mosquitos and other insect vectors of human disease,” he says. “If we could somehow boost vector insect immunity, it could decrease transmission of human disease like malaria.”

Related:

Fruit flies use alcohol as a drug to kill parasites

Fruit flies force their young to drink alcohol -- for their own good

What aphids can teach us about immunity

By Carol Clark

Parasitic wasps switch off the immune systems of fruit flies by draining calcium from the flies’ blood cells, a finding that offers new insight into how pathogens break through a host’s defenses.

“We believe that we have discovered an important component of cellular immunity, one that parasites have learned to take advantage of,” says Emory University biologist Todd Schlenke, whose lab led the research.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the results, showing how a wasp version of a conserved protein called SERCA, which normally functions to pump calcium from the cell cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum, can block a host’s cellular immune response.

“Before our study, there were hints that calcium signaling was important for blood cell activation following infection, but the fact that a parasite actively suppresses this signaling shows how important it is, Schlenke says. He adds that the insects can serve as a model for more complex human immune systems.

“It’s incredible the way the wasps use a protein in their venom to control the flies at a molecular level,” says Nathan Mortimer, a post-doctoral fellow in the Schlenke lab who conducted the experiments. “Instead of killing the fly immune cells, the wasps actually take over blood-cell signaling, manipulating the host’s cellular behavior from the bottom up.”

The research team also included Emory biologist Balint Kacsoh; Jeremy Goecks and James Taylor, from Emory’s departments of biology and mathematics and computer science; and James Mobley and Gregory Bowersock of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Fruit flies and the tiny wasps that parasitize them have co-evolved complex strategies of attack and defense. The wasps inject their eggs into the body cavities of fruit fly larvae, along with venom that aims to suppress the flies’ cellular immunity. If the flies fail to kill the wasp egg, a wasp larva hatches inside the fruit fly larva and begins to eat its host from the inside out.

“The wasp larvae have these sharp appendages, like the fingers of Edward Scissorhands, that they use to stick into the fly tissue and start eating,” Mortimer says. “It’s a brutal process.”

In previous research, the Schlenke lab has shown how fruit flies sometimes use alcohol in rotting fruit as a drug to kill the wasps.

In the current study, the researchers focused on the molecular attack strategies of the wasps. After sequencing the transcriptome of the newly described wasp species Ganaspis sp.1, they took a proteomic approach to identify peptide sequences out of the wasp’s venom gland, which they could then link back to full-length transcript sequences.

“We found that the venom of Ganaspis sp.1 is a toxic cocktail of 170 different proteins,” Schlenke says, “but the most prominent component was the SERCA calcium pump protein. That really surprised us.”

Wasps win: Arrows point to wasp larvae that have successfully blocked the fruit-fly immune response and are eating the tissue of the fruit fly.

Calcium pumps are found in the membranes of every living cell of every animal, and are needed to maintain ionic homeostasis and cellular stability. One type of pump moves calcium ions out of the endoplasmic reticulum and into the cytoplasm where they transmit signals that activate other proteins. The SERCA calcium pump operates in the opposite direction, sucking calcium ions out of the cytoplasm and back into storage.

“We wondered why the wasps would inject the flies with a protein that the flies already have, and that every cell needs to function,” Schlenke says. “How could that be an infection strategy?”

The researchers knew of studies suggesting that a calcium burst in cytoplasm is associated with the activation of human blood cells. They wondered if something similar was happening with the flies.

Mortimer conducted experiments on a transgenic fly strain with cells that fluoresce in the presence of calcium. He found that the fly blood cells release a burst of calcium into their cytoplasm, and that this activates the blood cells to start homing in on the wasp eggs. Genetically increasing or decreasing blood-cell calcium levels makes the flies more or less resistant to the parasite infection.

“The wasp venom prevents this calcium burst, and it’s like the fly blood cells don’t realize they’re supposed to be responding to infection,” Mortimer says. “The venom essentially sucks the calcium out of the fly’s blood cells.”

The experiments showed that the wasp venom is specifically targeted to the fly blood cells, and has no effect on other cells.

An unresolved question is how a SERCA protein, which is hydrophobic and normally resides in an oily membrane, moves out of a wasp venom cell and makes its way into a fly blood cell.

“We have no idea how it works,” Schlenke says, “but somehow this calcium pump moves through all these environments and finds its way into its target cells.”

The researchers hypothesize that virus-like particles in the wasp’s venom may be involved. “If they aren’t really viruses, they seem to be some virus-like thing that the wasp has invented,” Schlenke says. “It’s pure speculation, but we think maybe the wasps use these particles as delivery vehicles for the calcium pumps.”

Previous research has established that fruit fly immune signaling pathways have homologues in humans, making fruit flies a valuable model for learning about human immunity. That work led to the award of the 2011 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine to Jules Hoffmann, a fruit fly immunologist.

Studying the wasp-fly battle for survival at the molecular level provides a powerful new tool for unlocking more secrets of immunity that could apply to human health, Mortimer says.

“I’m also interested in using the flies to understand more about the immune systems of mosquitos and other insect vectors of human disease,” he says. “If we could somehow boost vector insect immunity, it could decrease transmission of human disease like malaria.”

Related:

Fruit flies use alcohol as a drug to kill parasites

Fruit flies force their young to drink alcohol -- for their own good

What aphids can teach us about immunity

Tags:

Biology,

Chemistry,

Ecology,

Environmental Studies,

Health

Friday, May 17, 2013

Star Trek and the ethics of space exploration

Who owns the moon? Is it fair to send people on a one-way trip to Mars? Can doctors safeguard medical experiments in other environments? These are just a few of the ethical questions confronting the human race as we continue to explore space.

The Emory Looks at Hollywood series examines these questions in context of the new Paramount Pictures movie "Star Trek Into Darkness," the latest in the long-running Star Trek story. Watch the video above as Paul Root Wolpe, Director of the Center for Ethics at Emory and the first Senior Bioethicist for NASA, discusses the ethics of space exploration.

Related: Scientist tackles the ethics of space travel

Tags:

Bioethics,

Health,

Physics,

Science and Art/Media

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Think you can win Powerball? Don't bet on it

The Powerball jackpot is up to $475 million, the second-largest in the lottery's history. Lottery officials put the odds of winning at one in 195 million, "meaning you are 251 times more likely to be hit by lightning," reports Alan Farnham of ABC's Good Morning America.

Below is an excerpt from Farnham's report:

"Skip Garibaldi, a professor of mathematics at Emory University in Atlanta, provides additional perspective: You are more likely to die from all of the following than you are to win tonight's drawing: be hit by a falling coconut, be blown up by fireworks, or be eaten by flesh-eating bacteria.

"Even though he knows the odds all too well, Garibaldi says that he has played past lotteries. 'When it gets big, I'll buy a couple of tickets. It's kind of exciting. You get this feeling of anticipation. You get to think about the fantasy.'

"Writing for the New York Post, Garibaldi recently reviewed the book 'Brain Trust,' in which 93 scientists give advice on subjects that include how to win the lottery.

"Their advice, he says, includes the following:

"Pick the most unpopular numbers. Avoid, for example, numbers thought to be 'lucky,' such as 7, 13, 23 and 32.

"Don't pick the number 1. It's on about 15 percent of all tickets.

"Do pick the 'especially overlooked' number 46.

"Garibaldi's own advice: Look for a jackpot that's rolled over at least five times yet still remains below $40 million. And be sure not to overlook state lotteries, which have fewer people competing for their pots."

Read the full report on the GMA website.

Related:

Lottery study zeros in on risk

Below is an excerpt from Farnham's report:

"Skip Garibaldi, a professor of mathematics at Emory University in Atlanta, provides additional perspective: You are more likely to die from all of the following than you are to win tonight's drawing: be hit by a falling coconut, be blown up by fireworks, or be eaten by flesh-eating bacteria.

"Even though he knows the odds all too well, Garibaldi says that he has played past lotteries. 'When it gets big, I'll buy a couple of tickets. It's kind of exciting. You get this feeling of anticipation. You get to think about the fantasy.'

"Writing for the New York Post, Garibaldi recently reviewed the book 'Brain Trust,' in which 93 scientists give advice on subjects that include how to win the lottery.

"Their advice, he says, includes the following:

"Pick the most unpopular numbers. Avoid, for example, numbers thought to be 'lucky,' such as 7, 13, 23 and 32.

"Don't pick the number 1. It's on about 15 percent of all tickets.

"Do pick the 'especially overlooked' number 46.

"Garibaldi's own advice: Look for a jackpot that's rolled over at least five times yet still remains below $40 million. And be sure not to overlook state lotteries, which have fewer people competing for their pots."

Read the full report on the GMA website.

Related:

Lottery study zeros in on risk

Wednesday, May 15, 2013

Poet Rita Dove on the chemistry of art and science

Asking a poet to give a commencement keynote seems like “both a no-brainer and a curious dare,” Rita Dove told Emory’s class of 2013.

A Pulitzer Prize winner and former U.S. Poet Laureate, Dove spoke of “the interconnectedness of all knowledge.” She warned that institutions of higher learning that diminish liberal arts programs in favor of business, law, medicine and scientific research are making a big mistake:

“How did we end up in this tug of war anyway? When was it decided that the sciences and the arts were adversaries? I myself come from a family of left-brainers. Two siblings are in computer sciences, another has a chemistry degree, and my father broke the race barrier in the rubber industry in the early 50s as the first African-American research chemist at Goodyear Tire and Rubber.

“Our house was littered with scientific paraphernalia. And if I got stuck in math homework, and asked my dad for help, he’d whip out his slide rule. I bet many of you don’t even know what a slide rule is, but trust me, it was daunting. And he would demonstrate three different ways to solve for X. Even though I was in fifth grade, I wouldn’t study trigonometry for many years, and didn’t even know how to spell 'cosine.' I might not have fully realized it at the time, but my father was trying to show me there can be several different ways to assess and interpret a situation, and multiple approaches to a solution. Math could have different points of view, just like characters in a Shakespeare play.”

Years later, Dove recalled, she was sitting on an overcrowded train pushing through snowbound New England. After some small talk, her seatmate asked her what she did for a living. She hesitated, then told him she was a poet. He was silent.

“And what do you do?” she retorted.

“The same hesitation until he replied, ‘I’m a microbiologist.' And then he blurted out, 'I don’t usually tell people that. They just freeze up and say something like, gee, that’s heavy, as if I was going to ask them to recite the periodic table.’

“And I said, ‘That’s pretty much the way people react when I tell them I’m a poet.’

“So we had a good laugh. And then I suggested, 'Okay, let’s give it a shot. Explain to me what your research is like, and then I’ll tell you what I’m working on now.'

“So we exchanged stories. And his was a perfectly poetic description of taking a walk along a strand of DNA, to look for anything that was out of place among the scenery. Those were his very words.”

We would all languish without our imaginations, and the language to bring it to life, Dove said.

“The mind is informed by the spirit of play and every discipline is peppered with vivid terminology. Fractal geometry has dragon curves and physics has Swiss cheese cosmology. There are lady slippers in botany. Football has wing backs, buttonholes and coffin corners. There are doglegs on golf courses and butterfly valves in automobiles. And when there are no words for what we need, we make new ones up…

“Here at Emory, you’ve been trained in your individual fields, but you’ve also been exposed to a range of disciplines and encouraged to explore new ideas.

“Whether you end up as a politician or a painter, a novelist or a nurse or a neurologist, this you all have in common. You have learned how to pursue thoughts and ideas and, hopefully, you’ve grown to love that pursuit.”

Dove concluded by reading her poem “Dawn Revisited,” which included the line:

“The whole sky is yours to write on, blown open to a blank page.”

Related:

Science grads set to change the world

Tibetan monks learn about science and 'riding shotgun'

Monday, May 13, 2013

Tibetan monks learn about science and 'riding shotgun'

Among the more than 4,200 graduates at Emory’s commencement were six Tibetan monks – the first group of monastics to complete a curriculum of modern science training at the behest of the Dalai Lama.

The Emory-Tibet Science Initiative aims to bring the best of Western science to the monastics, while sharing insights from Tibetan meditative practices with the Western world.

When they arrived on the Emory campus three years ago, the monks had little or no scientific training and limited English. Now the monks are returning to their monasteries in Dharamsala, India, to help teach other monks and nuns about biology, neuroscience, physics and math.

“We have a huge responsibility because we are the first to do this,” Lodoe Sangpo told the Atlanta Journal Constitution. “We must do as much as we can because this is His Holiness’ vision.”

Watch the video, above, to hear the monks describe their time at Emory, and some of their new favorite English words and phrases, like “riding shotgun.”

A new cohort of monks arrives at Emory in August for the ongoing program, which includes the creation of modern science textbooks in the Tibetan language.

The Dalai Lama himself returns to Emory in October. In addition to on-campus teaching and conversations with students, he will give two public talks at the Arena at Gwinnett Center.

Related:

Monks + scientists = new body of thought

Where science meets spirituality

Are hugs the new drugs?

Thursday, May 9, 2013

Science grads set to change the world

When Katie Dickerson looks back on the Katie of four years ago, she hardly recognizes her. "This has truly been a transformative place for me— the people I've met and the experiences I've had," the Emory senior says.

A double major in neuroscience and behavioral biology, anthropology and human biology, and a global health, culture and society minor, Dickerson was one of four seniors selected to pursue master's level work at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland as a Bobby Jones Scholar next year.

She plans to study neural and behavioral sciences and will focus her research on learning about episodic memory in children to see if the likelihood of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's or Parkinson's can be predicted.

Ultimately, she would like to go to medical school. Through volunteer work in Ghana, she saw "how much good there is to be done in the world with a medical degree."

Dickerson also won the Marion Luther Brittain Award, Emory's highest student honor, given for service rendered to the university without expectation of reward or recognition. Read more about Dickerson in Emory Report.

Emory senior Eduardo “Eddie” Garcia also excelled as a scholar, and as the founder of a medical interpretation service that has assisted hundreds of Atlanta’ immigrants and refugees. In recognition of his service, Garcia is this year’s recipient of the Lucius Lamar McMullan Award, which comes with $25,000, no strings attached.

Garcia is graduating with a major in chemistry and a minor in global health, culture and society. He will attend the School of Medicine at Texas Tech University next year and hopes to become a family physician dedicated to underserved communities.

Garcia spent the first 12 years of his life in Mexico until his family immigrated to El Paso, Texas, where he graduated from high school. He says his family and his Catholic faith motivate and push him to do his best and to serve others.

"My parents sacrificed everything to give us better opportunities. We didn't have a lot but we always had enough. They always taught me to be thankful for what you have, and when you receive blessings, you have an obligation to work to share those blessings and bless others," he says. Read more about Garcia in Emory Report.

Congratulations to all of Emory’s 2013 graduating seniors!

Click here to read a sampling of the original research projects the class of 2013 undertook, from distinguishing feral and managed honey bees using stable carbon isotopes, to the effect of Internet usage on media freedom in China.

Related:

Scholar reads the classics -- and bones

Burning with passion for the world

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

A psychoanalysis of 'The Great Gatsby'

Before there was “Keeping Up with the Kardashians” there was the ostentatious fictional protagonist in “The Great Gatsy,” says Jared DeFife, a clinical psychologist and Emory assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral studies.

So who exactly was Jay Gatsby? The "self-made man" archetype created by novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald is set to get renewed attention when portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio in a movie releasing this weekend.

To understand the underlying character of Gatsby, DeFife says it’s important to think about two primary emotions: Shame and grief.

Gatsby’s lavish displays of wealth are what psychologists call “a reaction formation” built around his shame of coming from a rather shiftless, lower-class family, DeFife says.

Shame involves worrying about how others see you, which is probably why eyes become a powerful symbol in the novel, DeFife adds. “The characters are relatively without guilt about their actions, but they are very afraid of being seen, and the negative things about them being seen.”

Gatsby also shows a complicated grief reaction to his loss of Daisy, who broke up with him when he went off to war. “What happens in distorted grief reactions is time sort of stops,” DeFife says. “Gatsby is really trying to reclaim that lost era. In fact, there’s a scene where he meets Daisy for the first time after so many years where he almost knocks a clock over on the mantle.”

Gatsby’s mindset remains back in the time when he was 17, and holds an idealized image of Daisy. “He’s stuck not being able to be able to go back to the past and recreate that life, and not being able to move forward, either, and that’s where his great tragedy comes in,” DeFife says.

Related:

'Batman' and the psychology of trauma

Filmmaker turns back the clock in 'Tick Tock'

So who exactly was Jay Gatsby? The "self-made man" archetype created by novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald is set to get renewed attention when portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio in a movie releasing this weekend.

To understand the underlying character of Gatsby, DeFife says it’s important to think about two primary emotions: Shame and grief.

Gatsby’s lavish displays of wealth are what psychologists call “a reaction formation” built around his shame of coming from a rather shiftless, lower-class family, DeFife says.

Shame involves worrying about how others see you, which is probably why eyes become a powerful symbol in the novel, DeFife adds. “The characters are relatively without guilt about their actions, but they are very afraid of being seen, and the negative things about them being seen.”

Gatsby also shows a complicated grief reaction to his loss of Daisy, who broke up with him when he went off to war. “What happens in distorted grief reactions is time sort of stops,” DeFife says. “Gatsby is really trying to reclaim that lost era. In fact, there’s a scene where he meets Daisy for the first time after so many years where he almost knocks a clock over on the mantle.”

Gatsby’s mindset remains back in the time when he was 17, and holds an idealized image of Daisy. “He’s stuck not being able to be able to go back to the past and recreate that life, and not being able to move forward, either, and that’s where his great tragedy comes in,” DeFife says.

Related:

'Batman' and the psychology of trauma

Filmmaker turns back the clock in 'Tick Tock'

Monday, May 6, 2013

'Iron Man' and the future of nanotechnology

How do you take a golden suit of armor to the next level? Tony Stark turns to nanotechnology in “Iron Man 3.” He undergoes injections of a super-soldier serum called Extremis that enhances strength and can regenerate limbs and cure wounds, so that he has super powers even when he’s not wearing his Iron Man suit.

While Extremis is an invention of comic books and Hollywood, scientists are actually working to develop similar “super serums” in the real world.

“Some of the features in the movie 'Iron Man' may be far-fetched, but other features will probably become a reality,” says Shuming Nie, chair of biomedical engineering at Emory and Georgia Tech and the director of the Emory-Georgia Tech Cancer Nanotechnology Center.

He cites a project supported by the U.S. Air Force involving nanoparticles that can amplify optical-detection sensitivity by 10 to the 14th fold.

Another promising area is targeted nanoparticles therapeutics, including a project under way at Emory, in collaboration with the University of Pennsylvania, to develop nanoparticle contrast agents.

“These are agents that you can inject into the human body two or three hours before surgery,” Nie explains. “A surgeon can then visualize where the tumors are, because they’re glowing. The surgeon can identify where the boundaries are, where to cut, and whether there is any residue tumor left.”

Major efforts are ongoing to develop nanotechnology applications for use in medicine, biology, energy and environmental science.

“The most amazing applications are probably going to be in the medical field,” Nie says. "To design anything that works inside the human body is enormously challenging, because the human body is immensely complex. However, our imaginations are also unlimited. So if we work together, I think certainly in the next generation we'll have some of these nanoparticles with specialized functions able to do very unusual things in the human body."

Related:

The science and ethics of X-Men

Physics flies off the rails in 'Unstoppable'

Is 'Iron Man' suited for reality?

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Bone to be wild: Fleshing out a career devoted to skeletons and people

By Carol Clark

Dennis Van Gerven was flattered when George Armelagos handed him a human femur bone from a burnt-out crime scene and asked him to take it home for analysis. The two anthropologists were in Philadelphia for a conference and a criminal investigator had sought Armelagos’ expertise in piecing together details about dead people by studying their bones.

As Armelagos went through the airport security checkpoint, he turned to Van Gerven, who was next in line, and said loudly, “Be sure and tell them that your wife was alive when you saw her last.”

Then he kept walking, leaving Van Gerven to face the security agent alone.

“My bag goes through the X-ray and you can see this bone in my suitcase,” Van Gerven recalls. “The agent asked, ‘What’s that?’ I said, ‘It’s a bone.’ He said, ‘Oh,” and lets me go through.”

The story was one of many recounted during a day-long session devoted to the research, mentorship and mischief of Armelagos at the recent annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. The session, entitled “Bone to Be Wild,” drew dozens of students and colleagues to Knoxville to celebrate Armelagos’ ongoing career of 50 years.

“I was overwhelmed,” says Armelagos, Goodrich C. White Professor of Anthropology at Emory. “It was surreal, sort of like an out-of-body experience, hearing everyone talk about me.”

Former students presented 22 scientific posters describing how Armelagos involved them in pioneering work in wide-ranging topics that changed the field of anthropology, from our understanding of race and racism to the influence of agriculture, diet and stress on the health of individuals and across populations.

While still a graduate student in the 1960s, Armelagos was part of a team that excavated ancient skeletons from Sudanese Nubia, so the bones would not be lost forever when the Nile was dammed. The amount of scholarship done by Armelagos, his students and colleagues over the decades have made the Sudanese Nubians the most studied archeological population in the world.

“One of his main contributions is the marriage of biology with archeology,” says Debra Martin, a co-organizer of the session. “Previously, archeologists would retrieve human remains but then send them off to medical schools or other places interested in the biology. George kept the burials in the archeological context so that as you analyzed the bones, you were also studying a past way of life.”

He uses this approach to ask “some of these really big questions of our time,” Martin says. “He showed how the past sheds light not only on the origins of human conditions, but where we’re going. We see that racism, for example, is as deeply embedded in human behavior as it’s ever been, and yet it’s not in our biology or genes. It’s in the way that we organize ourselves culturally that we create some of these problems around race, nutrition, health and violence.”

Armelagos, in his lab during the 1980s, is still teaching and publishing at 77.

Martin, now a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, studied under Armelagos at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Armelagos has mentored over 30 PhD students, and many of them have gone on to become chairs of their departments or deans at their universities.

As a freshman at the University of Utah in 1965, Van Gerven was among Armelagos’ first group of students.

“George was a social force on that campus,” Van Gerven says. He recalls Armelagos holding court in a dining commons area, where he would often stay late into the evening, energized by caffeine and conversations with students.

“You’d see a crowd in the center of the room,” Van Gerven says. “And you’d work your way through to the middle of it, and there would be George. He’s truly interested in everybody and everything.”

When Armelagos moved to the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Van Gerven followed for his PhD. Armelagos didn’t just give his graduate students food for thought. He cooked them gourmet meals and turned his home into an extension of the classroom. “He had a huge, long table where he would feed all of us,” Van Gerven says.

The larger the word, the more frequently it was mentioned by former students asked about Armelagos' influence on anthropology. (Survey conducted by Ventura Perez and Heidi Bauer-Clapp of University of Massachusetts, Amherst.)

Armelagos’ knack for demystifying research has set many undergraduates onto life-changing paths.

“The first article we published together came out in 1968, and we’re working on a book right now,” Van Gerven says. “I learned everything from him. He taught me how to think, he taught me how to work and to be passionate. He made me love this stuff.”

Armelagos joined Emory in 1994, and helped solidify the University’s reputation as a national leader in the bio-cultural approach to anthropology. So far, more than 80 of his Emory students have presented papers or published research as undergraduates.

Emory graduate Kristin Harper with Armelagos at "Bone to be Wild." Under his tutelage, Harper published the first phylogenetic approach to the centuries-old debate over the origins of syphilis.

Molly Zuckerman came to Emory for a PhD because she was inspired by Armelagos’ work on the evolution of syphilis. She soon found herself in England, tracking down human remains in the basements of out-of-the-way museums to research the origins of the disease.

“George ushered in a paleopathology movement that’s since become widespread, the idea that you need to orient your work to have a larger meaning than just documenting a particular disease,” Zuckerman says. “If you’re going to mess with the bones of someone’s ancestors, it should benefit contemporary populations. So you need to look at things in an evolutionary and ecological and sociological context.”

A co-organizer of the “Bone to be Wild” session, Zuckerman completed her dissertation “Sex, Society and Syphilis” in 2010 and is now an assistant professor at Mississippi State.

A sucker for kids: Armelagos with Henry, son of Emory anthropologist Craig Hadley.

Armelagos, meanwhile, continues to teach and publish prolifically at 77. “I enjoy what I’m doing,” he says. “It’s energizing. How could I get tired of it?” (Listen to a podcast of Armelagos reading an excerpt from his most recent book, "St. Catherine's Island: The Untold Story of People and Place.")

“In terms of energy and enthusiasm, George can kick my ass on his worst day, and I’m 10 years younger,” says Van Gerven, who recently retired from the University of Colorado. “I’m not sure George is from this planet. But he’s one of the most wonderful and brilliant beings I’ve ever known. And he’s completely crazy.”

Among the secrets to a long and happy career, Armelagos says, is to have fun and not take yourself too seriously. Even after decades in bio-archeology, he still laughs at skeleton jokes.

And, although he has extensively researched the relationship between diet and health, Armelagos is famous for over indulging, both himself and others.

Van Gerven recalls when Armelagos was visiting him and his family years ago and they stopped in a bank. “There was a jar of suckers on the counter, and George grabbed about 15 of them and handed them to my son, Jessie, who was three years old,” Van Gerven says.

Another customer in the bank scolded Armelagos, telling him shouldn't give his kid so much candy. Armelagos replied, ‘He's not my kid.’” The customer said, "Okay."

Related:

Skeletons point to Columbus voyage for syphilis origins

Dawn of agriculture took toll on health

Ancient brewers tapped antibiotic secrets

Telling the story of St. Catherine's Island

Credits: Top photo, iStockphoto.com. All others courtesy of George Armelagos.

Tags:

Anthropology,

Biology,

Ecology,

Environmental Studies,

Health,

Humor/Fun,

Sociology

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)