By Carol Clark

“Wherever I travel, I take my bone drill with me,” says Kendra Sirak.

An Emory PhD candidate in anthropology, Sirak has developed a specialized technique for drilling into ancient skulls to remove DNA samples. She’s flown to more than a dozen countries and drilled more than 1,000 skulls, perfecting the technique.

“No one at customs has ever questioned me about why I’m carrying a gigantic drill in my suitcase,” she notes.

Sirak has the distinction of being the last graduate student of the late George Armelagos, Goodrich C. White Professor of Anthropology. Armelagos, who died in 2014 at the age of 77, was one of the founders of the field of paleopathology.

He spent decades working with graduate students to study the bones of ancient Sudanese Nubians to learn about patterns of health, illness and death in the past. The only piece missing in studies of this population was genetic analysis. So in 2013, Armelagos sent Sirak to one of the best ancient DNA labs in the world, University College Dublin, with samples of the Nubian bones.

“I had no interest in genetics,” says Sirak, who was passionate about studying human bones and paleopathology. “But George believed DNA was going to become a critical part of anthropological research.”

|

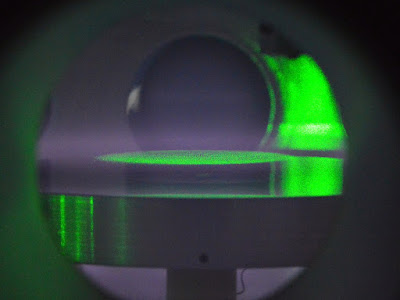

| Sirak drills the base of an ancient skull. |

As genetic sequencing techniques keep improving, anthropology and DNA analysis are becoming increasingly complementary. In 2015, another breakthrough occurred when researchers realized that the petrous bone consistently yielded the most DNA from ancient skeletons. This pyramid-shaped bone houses several parts of the inner ear related to hearing and balance.

But the way the petrous bone is wedged into the skull makes it difficult to access without shattering the cranium. Understandably, museum curators were reluctant to allow DNA researchers to tamper with rare, fragile ancient skulls.

So Sirak set about developing a technique to drill into a skull and reach the petrous bone in the most non-invasive way possible, while also getting enough bone powder for DNA analysis. The journal Biotechniques recently published her method, which involves drilling through the cranial base, where the spinal cord enters the skull.

“Hopefully, it will become the gold standard for both anthropology stewardship as well as DNA analysis,” Sirak says.

Sirak herself has the most experience in using the technique and her services have been in demand, as researchers seek to unlock secrets of ancient skeletons in museums and other collections.

Sirak’s trusty bone drill is a more modern version of the electric drill her father kept in the garage for household projects. Hers, however, has a foot pedal giving her precision control over the drill’s speed, and a flexible extension cord similar to what you might encounter in a dentist’s chair. The drill bits she uses range from 3.4 to 4.8 millimeters in diameter.

“Drilling an ancient skull can be nerve wracking,” Sirak says, “because you don’t want to be responsible for ruining a specimen. I’ve had museum curators watch me over my shoulder. Sometimes they are so close you can feel their breath on your neck.”

Besides drilling for DNA, she speaks at conferences, gives demonstrations and trains other researchers in her technique. “It’s a lot of fun to work with others who want to learn,” says Sirak, who has helped set up ancient DNA labs in India and China.

She is now finishing up her dissertation, a bioethnography of the ancient Nubians, and expects to graduate from Emory in June.

“Anthropological genetics is a huge and growing field,” Sirak says, acknowledging Armelagos for setting her on the path. “He was a good mentor. He introduced me to something that I didn’t know existed and let me run with it.”

Related:

Malawi yields oldest known DNA from Africa

Adding anthropology to genetics to study ancient DNA