The origami of disease, and of life: Research into the abnormal folding of proteins related to neurodegenerative conditions is providing insights into how life may emerge from a chemical system.

By Carol Clark

Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions involving abnormal folding of proteins, may help explain the emergence of life – and how to create it.

Researchers at Emory University and Georgia Tech demonstrated this connection in two new papers published by Nature Chemistry: “Design of multi-phase dynamic chemical networks” and “Catalytic diversity in self-propagating peptide assemblies.”

“In the first paper we showed that you can create tension between a chemical and physical system to give rise to more complex systems. And in the second paper, we showed that these complex systems can have remarkable and unexpected functions,” says David Lynn, a systems chemist in Emory’s Department of Chemistry who led the research. “The work was inspired by our current understanding of Darwinian selection of protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases.”

The Lynn lab is exploring ways to potentially control and direct the processes of these proteins – known as prions – adding to knowledge that might one day help to prevent disease, as well as open new realms of synthetic biology. For the current papers, Emory collaborated with the research group of Martha Grover, a professor in the Georgia Tech School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering, to develop molecular models for the processes.

“Modeling requires us to formulate our hypotheses in the language of mathematics, and then we use the models to design further experiments to test the hypotheses,” Grover says.

Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is well-established – organisms adapt over time in response to environmental changes. But theories about how life emerges – the movement through a pre-Darwinian world to the Darwinian threshold – remain murkier.

The researchers started with single peptides and engineered in the capacity to spontaneously form small proteins, or short polymers. “These protein polymers can fold into a seemingly endless array of forms, and sometimes behave like origami,” Lynn explains. “They can stack into assemblies that carry new functions, like prions that move from cell-to-cell, causing disease.”

This protein misfolding provided the model for how physical changes could carry information with function, a critical component for evolution. To try to kickstart that evolution, the researchers engineered a chemical system of peptides and coupled it to the physical system of protein misfolding. The combination results in a system that generates step-by-step, progressive changes, through self-driven environmental changes.

“The folding events, or phase changes, drive the chemistry and the chemistry drives the replication of the protein molecules,” Lynn says. “The simple system we designed requires only the initial intervention from us to achieve progressive growth in molecular order. The challenge now becomes the discovery of positive feedback mechanisms that allow the system to continue to grow.”

The research was funded by the McDonnell Foundation, the National Science Foundation’s Materials Science Directorate, Emory University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, the National Science Foundation’s Center for Chemical Evolution and the Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy.

Additional co-authors of the papers include: Toluople Omosun, Seth Childers, Dibyendu Das and Anil Mehta (Emory Departments of Chemistry and Biology); Ming-Chien Hsieh (Georgia Tech School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering); and Neil Anthony and Keith Berland (Emory Department of Physics).

Related:

Peptides may hold 'missing link' to life

Monday, February 27, 2017

Monday, February 20, 2017

Contact tracing, with indoor spraying, can curb dengue outbreak

A traditional Queenslander home in Cairns, Australia, is open to breezes, as well as to disease-bearing mosquitoes. (Photo via James Cook University.)

By Carol Clark

Contact tracing, combined with targeted, indoor residual spraying of insecticide, can greatly reduce the spread of the mosquito-borne dengue virus, finds a study led by Emory University.

In fact, this novel approach for the surveillance and control of dengue fever – spread by the same mosquito species that infects people with the Zika virus – was between 86 and 96 percent effective during one outbreak, the research shows. By comparison, vaccines for the dengue virus are only 30-to-70-percent effective, depending on the serotype of the virus.

Science Advances published the findings, which were based on analyses from a 2009 outbreak of dengue in Cairns, Australia.

“We’ve provided evidence for a method that is highly effective at preventing transmission of diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito in a developed, urban setting,” says the study’s lead author, Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, a disease ecologist in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences. “We’ve also shown the importance of human movement when conducting surveillance of these diseases.”

“The United States is facing continual threats from dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses,” says Sam Scheiner, director of the National Science Foundation’s Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases Program, which funded the research. “For now, the response is to intensively spray insecticides. This research shows that a more targeted approach can be more effective.”

While the method would likely not be applicable everywhere, Vazquez-Prokopec says that it may be viable to control Aedes-borne diseases in places with established health systems and similar environmental characteristics to Cairns, such as South Florida or other U.S. states at risk of virus introduction.

“The widespread transmission of dengue viruses, coupled with the birth defects associated with Zika virus, shows the dire need for as many weapons as possible in our arsenal to fight diseases spread by these mosquitos,” he says. “Interventions need to be context dependent and evaluated carefully and periodically.”

A public health worker collects Aedes mosquito larvae from water that has pooled on a tarp at a residence in Cairns, Australia.

During the dengue outbreak in Cairns, public health officials traced recent contacts of people with a confirmed infection – a surveillance method known as contact tracing. This method is commonly used for directly transmitted pathogens like Ebola or HIV, but rarely for outbreaks spread by mosquitos or other vectors.

Using mobility data from the known cases, public health workers targeted residences for indoor residual spraying, or IRS. Walls of the homes – from top to bottom – and dark, humid places where Aedes mosquitos might rest, were sprayed with an insecticide that lasts for months.

The method is time-consuming and labor intensive, and health officials were not able to reach all of the residences that were connected to the infected persons.

The researchers found that performing IRS in potential exposure locations reduced the probability of dengue transmission by at least 86 percent in those areas, in comparison to areas of potential exposures that did not have indoor spraying.

“The findings are important,” Vazquez-Prokopec says, “because they demonstrate one of the few measures that we have for the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce the transmission of dengue.”

Many times, he says, in the face of a dengue outbreak public health officials end up using trucks to spray insecticide – despite the lack of scientific evidence for the effectiveness of fogging from the streets to control Aedes aegypti mosquitos.

Quantifying the effectiveness of existing methods, and the context within which they work, can strengthen the vector-control arsenal. “We need to develop plans for outbreak containment that are context-specific,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

He is researching ways to scale up this intervention. While it now takes approximately half-an-hour to conduct indoor residual spraying in a single house, he would like to cut that time to as little as 10 minutes.

“We are evaluating how we can scale up and improve IRS for 21st-century urban areas,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

Co-authors of the study include researchers from Queensland Health, the Rollins School of Public Health and James Cook University, Cairns.

Related:

Zeroing in on 'super spreaders' and other hidden patterns of epidemics

Human mobility data may help curb urban epidemics

By Carol Clark

Contact tracing, combined with targeted, indoor residual spraying of insecticide, can greatly reduce the spread of the mosquito-borne dengue virus, finds a study led by Emory University.

In fact, this novel approach for the surveillance and control of dengue fever – spread by the same mosquito species that infects people with the Zika virus – was between 86 and 96 percent effective during one outbreak, the research shows. By comparison, vaccines for the dengue virus are only 30-to-70-percent effective, depending on the serotype of the virus.

Science Advances published the findings, which were based on analyses from a 2009 outbreak of dengue in Cairns, Australia.

“We’ve provided evidence for a method that is highly effective at preventing transmission of diseases carried by the Aedes aegypti mosquito in a developed, urban setting,” says the study’s lead author, Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, a disease ecologist in Emory’s Department of Environmental Sciences. “We’ve also shown the importance of human movement when conducting surveillance of these diseases.”

“The United States is facing continual threats from dengue, chikungunya and Zika viruses,” says Sam Scheiner, director of the National Science Foundation’s Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases Program, which funded the research. “For now, the response is to intensively spray insecticides. This research shows that a more targeted approach can be more effective.”

While the method would likely not be applicable everywhere, Vazquez-Prokopec says that it may be viable to control Aedes-borne diseases in places with established health systems and similar environmental characteristics to Cairns, such as South Florida or other U.S. states at risk of virus introduction.

“The widespread transmission of dengue viruses, coupled with the birth defects associated with Zika virus, shows the dire need for as many weapons as possible in our arsenal to fight diseases spread by these mosquitos,” he says. “Interventions need to be context dependent and evaluated carefully and periodically.”

A public health worker collects Aedes mosquito larvae from water that has pooled on a tarp at a residence in Cairns, Australia.

During the dengue outbreak in Cairns, public health officials traced recent contacts of people with a confirmed infection – a surveillance method known as contact tracing. This method is commonly used for directly transmitted pathogens like Ebola or HIV, but rarely for outbreaks spread by mosquitos or other vectors.

Using mobility data from the known cases, public health workers targeted residences for indoor residual spraying, or IRS. Walls of the homes – from top to bottom – and dark, humid places where Aedes mosquitos might rest, were sprayed with an insecticide that lasts for months.

The method is time-consuming and labor intensive, and health officials were not able to reach all of the residences that were connected to the infected persons.

The researchers found that performing IRS in potential exposure locations reduced the probability of dengue transmission by at least 86 percent in those areas, in comparison to areas of potential exposures that did not have indoor spraying.

“The findings are important,” Vazquez-Prokopec says, “because they demonstrate one of the few measures that we have for the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce the transmission of dengue.”

Many times, he says, in the face of a dengue outbreak public health officials end up using trucks to spray insecticide – despite the lack of scientific evidence for the effectiveness of fogging from the streets to control Aedes aegypti mosquitos.

Quantifying the effectiveness of existing methods, and the context within which they work, can strengthen the vector-control arsenal. “We need to develop plans for outbreak containment that are context-specific,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

He is researching ways to scale up this intervention. While it now takes approximately half-an-hour to conduct indoor residual spraying in a single house, he would like to cut that time to as little as 10 minutes.

“We are evaluating how we can scale up and improve IRS for 21st-century urban areas,” Vazquez-Prokopec says.

Co-authors of the study include researchers from Queensland Health, the Rollins School of Public Health and James Cook University, Cairns.

Related:

Zeroing in on 'super spreaders' and other hidden patterns of epidemics

Human mobility data may help curb urban epidemics

Tags:

Biology,

Climate change,

Community Outreach,

Ecology,

Health

Friday, February 17, 2017

How dads bond with toddlers: Brain scans link oxytocin to paternal nurturing

The findings show that "fathers, and not just mothers, undergo hormonal changes that are likely to facilitate increased empathy and motvation to care for their children," says Emory anthropologist James Rilling.

By Carol Clark

Fathers given boosts of the hormone oxytocin show increased activity in brain regions associated with reward and empathy when viewing photos of their toddlers, an Emory University study finds.

“Our findings add to the evidence that fathers, and not just mothers, undergo hormonal changes that are likely to facilitate increased empathy and motivation to care for their children,” says lead author James Rilling, an Emory anthropologist and director of the Laboratory for Darwinian Neuroscience. “They also suggest that oxytocin, known to play a role in social bonding, might someday be used to normalize deficits in paternal motivation, such as in men suffering from post-partum depression.”

The journal Hormones and Behavior published the results of the study, the first to look at the influence of both oxytocin and vasopressin – another hormone linked to social bonding – on brain function in human fathers.

A growing body of literature shows that paternal involvement plays a role in reducing child mortality and morbidity, and improving social, psychological and educational outcomes. But not every father takes a “hands-on” approach to caring for his children.

“I’m interested in understanding why some fathers are more involved in caregiving than others,” Rilling says. “In order to fully understand variation in caregiving behavior, we need a clear picture of the neurobiology and neural mechanisms that support the behavior.”

Researchers have long known that when women go through pregnancy they experience dramatic hormonal changes that prepare them for child rearing. Oxytocin, in particular, was traditionally considered a maternal hormone since it is released into the bloodstream during labor and nursing and facilitates the processes of birth, bonding with the baby and milk production.

More recently, however, it became clear that men can also undergo hormonal changes when they become fathers, including increases in oxytocin. Evidence shows that, in fathers, oxytocin facilitates physical stimulation of infants during play as well as the ability to synchronize their emotions with their children.

In order to investigate the neural mechanisms involved in oxytocin and paternal behavior, the Rilling lab used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to compare neural activity in men with and without doses of oxytocin, administered through a nasal spray. The participants in the experiment were all healthy fathers of toddlers, between the ages of one and two. While undergoing fMRI brain scans, each participant was shown a photo of his child, a photo of a child he did not know and a photo of an adult he did not know.

When viewing an image of their offspring, participants dosed with oxytocin showed significantly increased neural activity in brain systems associated with reward and empathy, compared to placebo. This heightened activity (in the caudate nucleus, dorsal anterior cingulate and visual cortex) suggests that doses of oxytocin may augment feelings of reward and empathy in fathers, as well as their motivation to pay attention to their children.

Surprisingly, the study results did not show a significant effect of vasopressin on the neural activity of fathers, contrary to the findings of some previous studies on animals.

Research in prairie voles, which bond for life, for instance, has shown that vasopressin promotes both pair-bonding and paternal caregiving. “It could be that evolution has arrived at different strategies for motiving paternal caregiving in different species,” Rilling says.

Co-authors of the study include Ting Li (Emory Anthropology), Xu Chen (Emory Anthropology and the School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences), Jennifer Mascaro (Emory School of Medicine Department of Family and Preventive Medicine) and Ebrahim Haroon (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences)

Related:

Testes size correlates with men's involvement in toddler care

A brainy time traveler

By Carol Clark

Fathers given boosts of the hormone oxytocin show increased activity in brain regions associated with reward and empathy when viewing photos of their toddlers, an Emory University study finds.

“Our findings add to the evidence that fathers, and not just mothers, undergo hormonal changes that are likely to facilitate increased empathy and motivation to care for their children,” says lead author James Rilling, an Emory anthropologist and director of the Laboratory for Darwinian Neuroscience. “They also suggest that oxytocin, known to play a role in social bonding, might someday be used to normalize deficits in paternal motivation, such as in men suffering from post-partum depression.”

The journal Hormones and Behavior published the results of the study, the first to look at the influence of both oxytocin and vasopressin – another hormone linked to social bonding – on brain function in human fathers.

A growing body of literature shows that paternal involvement plays a role in reducing child mortality and morbidity, and improving social, psychological and educational outcomes. But not every father takes a “hands-on” approach to caring for his children.

“I’m interested in understanding why some fathers are more involved in caregiving than others,” Rilling says. “In order to fully understand variation in caregiving behavior, we need a clear picture of the neurobiology and neural mechanisms that support the behavior.”

Researchers have long known that when women go through pregnancy they experience dramatic hormonal changes that prepare them for child rearing. Oxytocin, in particular, was traditionally considered a maternal hormone since it is released into the bloodstream during labor and nursing and facilitates the processes of birth, bonding with the baby and milk production.

More recently, however, it became clear that men can also undergo hormonal changes when they become fathers, including increases in oxytocin. Evidence shows that, in fathers, oxytocin facilitates physical stimulation of infants during play as well as the ability to synchronize their emotions with their children.

In order to investigate the neural mechanisms involved in oxytocin and paternal behavior, the Rilling lab used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to compare neural activity in men with and without doses of oxytocin, administered through a nasal spray. The participants in the experiment were all healthy fathers of toddlers, between the ages of one and two. While undergoing fMRI brain scans, each participant was shown a photo of his child, a photo of a child he did not know and a photo of an adult he did not know.

When viewing an image of their offspring, participants dosed with oxytocin showed significantly increased neural activity in brain systems associated with reward and empathy, compared to placebo. This heightened activity (in the caudate nucleus, dorsal anterior cingulate and visual cortex) suggests that doses of oxytocin may augment feelings of reward and empathy in fathers, as well as their motivation to pay attention to their children.

Surprisingly, the study results did not show a significant effect of vasopressin on the neural activity of fathers, contrary to the findings of some previous studies on animals.

Research in prairie voles, which bond for life, for instance, has shown that vasopressin promotes both pair-bonding and paternal caregiving. “It could be that evolution has arrived at different strategies for motiving paternal caregiving in different species,” Rilling says.

Co-authors of the study include Ting Li (Emory Anthropology), Xu Chen (Emory Anthropology and the School of Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences), Jennifer Mascaro (Emory School of Medicine Department of Family and Preventive Medicine) and Ebrahim Haroon (Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences)

Related:

Testes size correlates with men's involvement in toddler care

A brainy time traveler

Friday, February 10, 2017

Brazilian peppertree packs power to knock out antibiotic-resistant bacteria

The weed whisperer: Ethnobotanist Cassandra Quave uncovered a medicinal mechanism in berries of the Brazilian peppertree. The plant is a weedy invasive species in Florida, but valued by traditional healers in the Amazon as a treatment for infections. (Photos by Ann Bordon, Emory Photo/Video)

By Carol Clark

The red berries of the Brazilian peppertree – a weedy, invasive species common in Florida – contain an extract with the power to disarm dangerous antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria, scientists at Emory University have discovered.

The journal Scientific Reports published the finding, made in the lab of Cassandra Quave, an assistant professor in Emory’s Center for the Study of Human Health and in the School of Medicine’s Department of Dermatology.

“Traditional healers in the Amazon have used the Brazilian peppertree for hundreds of years to treat infections of the skin and soft tissues,” Quave says. “We pulled apart the chemical ingredients of the berries and systematically tested them against disease-causing bacteria to uncover a medicinal mechanism of this plant.”

The researchers showed that a refined, flavone-rich composition extracted from the berries inhibits formation of skin lesions in mice infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus auereus (MRSA). The compound works not by killing the MRSA bacteria, but by repressing a gene that allows the bacteria cells to communicate with one another. Blocking that communication prevents the cells from taking collective action, a mechanism known as quorum quenching.

“It essentially disarms the MRSA bacteria, preventing it from excreting the toxins it uses as weapons to damage tissues,” Quave says. “The body’s normal immune system then stands a better chance of healing a wound.”

The discovery may hold potential for new ways to treat and prevent antibiotic-resistant infections, a growing international problem. Antibiotic-resistant infections annually cause at least two million illnesses and 23,000 deaths in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The United Nations last year called antibiotic-resistant infections a “fundamental threat” to global health and safety, citing estimates that they cause at least 700,000 deaths each year worldwide, with the potential to grow to 10 million deaths annually by 2050.

Blasting deadly bacteria with drugs designed to kill them is helping to fuel the problem of antibiotic resistance. Some of the stronger bacteria may survive these drug onslaughts and proliferate, passing on their genes to offspring and leading to the evolution of deadly “super bugs.”

In contrast, the Brazilian peppertree extract works by simply disrupting the signaling of MRSA bacteria without killing it. The researchers also found that the extract does not harm the skin tissues of mice, or the normal, healthy bacteria found on skin.

“In some cases, you need to go in heavily with antibiotics to treat a patient,” Quave says. “But instead of always setting a bomb off to kill an infection, there are situations where using an anti-virulence method may be just as effective, while also helping to restore balance to the health of a patient. More research is needed to better understand how we can best leverage anti-virulence therapeutics to improve patient outcomes.”

Quave, a leader in the field of medical ethnobotany and a member of the Emory Antibiotic Resistance Center, studies how indigenous people incorporate plants in healing practices to uncover promising candidates for new drugs.

Cassandra Quave with her lab manager James Lyles, a co-author of the Brazilian peppertree study and a post-doctoral fellow at Emory.

The Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia) is native to South America but thrives in subtropical climates. It is abundant in much of Florida, and has also crept into southern areas of Alabama, Georgia, Texas and California. Sometimes called the Florida holly or broad leaf peppertree, the woody plant forms dense thickets that crowd out native species.

“The Brazilian peppertree is not some exotic and rare plant found only on a remote mountaintop somewhere,” Quave says. “It’s a weed, and the bane of many a landowner in Florida.”

From an ecological standpoint, it makes sense that weeds would have interesting chemistry, Quave adds. “Persistent, weedy plants tend to have a chemical advantage in their ecosystems, which may help protect them from diseases so they can more easily spread in a new environment.”

The study's co-authors include Amelia Muhs and James Lyles (Emory Center for the Study of Human Health); Kate Nelson (Emory School of Medicine); and Corey Parlet, Jeffery Kavanaugh and Alexander Horswill (University of Iowa). The laboratory experiments were conducted in collaboration between the Quave and Horswill labs with funding from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health.

The Quave lab is now doing additional research to confirm the safest and most effective means of using the Brazilian peppertree extract. The next step would be pre-clinical trials to test its medicinal benefits. “If the pre-clinical trials are successful, we will apply for an application to pursue clinical trials, under the Food and Drug Administration’s botanical drug pathway,” Quave says.

The Brazilian peppertree finding follows another discovery made by the Quave lab in 2015: The leaves of the European chestnut tree also contain ingredients with the power to disarm staph bacteria without increasing its drug resistance.

While both the Brazilian peppertree and chestnut tree extracts disrupted the signaling needed for quorum quenching, the two extracts are made up of different chemical compounds.

“The latest classes of antibiotics introduced to the market were actually discovered between the 1950s and 1980s,” Quave says. “Scientists have just been building off the same building blocks of earlier classes and modifying them slightly to create new antibiotics. Examining the extracts of plants used by traditional healers for infections may open up discovery of new chemical scaffolds for drug design, and provide important pathways for battling antibiotic-resistance.”

Related:

Chestnut leaves yield extract that disarms deadly bacteria

Tapping traditional remedies to fight modern super bugs

A future without antibiotics?

By Carol Clark

The red berries of the Brazilian peppertree – a weedy, invasive species common in Florida – contain an extract with the power to disarm dangerous antibiotic-resistant staph bacteria, scientists at Emory University have discovered.

The journal Scientific Reports published the finding, made in the lab of Cassandra Quave, an assistant professor in Emory’s Center for the Study of Human Health and in the School of Medicine’s Department of Dermatology.

“Traditional healers in the Amazon have used the Brazilian peppertree for hundreds of years to treat infections of the skin and soft tissues,” Quave says. “We pulled apart the chemical ingredients of the berries and systematically tested them against disease-causing bacteria to uncover a medicinal mechanism of this plant.”

|

| Brazilian peppertree, Schinus terebinthifolia |

“It essentially disarms the MRSA bacteria, preventing it from excreting the toxins it uses as weapons to damage tissues,” Quave says. “The body’s normal immune system then stands a better chance of healing a wound.”

The discovery may hold potential for new ways to treat and prevent antibiotic-resistant infections, a growing international problem. Antibiotic-resistant infections annually cause at least two million illnesses and 23,000 deaths in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The United Nations last year called antibiotic-resistant infections a “fundamental threat” to global health and safety, citing estimates that they cause at least 700,000 deaths each year worldwide, with the potential to grow to 10 million deaths annually by 2050.

Blasting deadly bacteria with drugs designed to kill them is helping to fuel the problem of antibiotic resistance. Some of the stronger bacteria may survive these drug onslaughts and proliferate, passing on their genes to offspring and leading to the evolution of deadly “super bugs.”

In contrast, the Brazilian peppertree extract works by simply disrupting the signaling of MRSA bacteria without killing it. The researchers also found that the extract does not harm the skin tissues of mice, or the normal, healthy bacteria found on skin.

“In some cases, you need to go in heavily with antibiotics to treat a patient,” Quave says. “But instead of always setting a bomb off to kill an infection, there are situations where using an anti-virulence method may be just as effective, while also helping to restore balance to the health of a patient. More research is needed to better understand how we can best leverage anti-virulence therapeutics to improve patient outcomes.”

Quave, a leader in the field of medical ethnobotany and a member of the Emory Antibiotic Resistance Center, studies how indigenous people incorporate plants in healing practices to uncover promising candidates for new drugs.

Cassandra Quave with her lab manager James Lyles, a co-author of the Brazilian peppertree study and a post-doctoral fellow at Emory.

The Brazilian peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolia) is native to South America but thrives in subtropical climates. It is abundant in much of Florida, and has also crept into southern areas of Alabama, Georgia, Texas and California. Sometimes called the Florida holly or broad leaf peppertree, the woody plant forms dense thickets that crowd out native species.

“The Brazilian peppertree is not some exotic and rare plant found only on a remote mountaintop somewhere,” Quave says. “It’s a weed, and the bane of many a landowner in Florida.”

From an ecological standpoint, it makes sense that weeds would have interesting chemistry, Quave adds. “Persistent, weedy plants tend to have a chemical advantage in their ecosystems, which may help protect them from diseases so they can more easily spread in a new environment.”

The study's co-authors include Amelia Muhs and James Lyles (Emory Center for the Study of Human Health); Kate Nelson (Emory School of Medicine); and Corey Parlet, Jeffery Kavanaugh and Alexander Horswill (University of Iowa). The laboratory experiments were conducted in collaboration between the Quave and Horswill labs with funding from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, National Institutes of Health.

The Quave lab is now doing additional research to confirm the safest and most effective means of using the Brazilian peppertree extract. The next step would be pre-clinical trials to test its medicinal benefits. “If the pre-clinical trials are successful, we will apply for an application to pursue clinical trials, under the Food and Drug Administration’s botanical drug pathway,” Quave says.

The Brazilian peppertree finding follows another discovery made by the Quave lab in 2015: The leaves of the European chestnut tree also contain ingredients with the power to disarm staph bacteria without increasing its drug resistance.

While both the Brazilian peppertree and chestnut tree extracts disrupted the signaling needed for quorum quenching, the two extracts are made up of different chemical compounds.

“The latest classes of antibiotics introduced to the market were actually discovered between the 1950s and 1980s,” Quave says. “Scientists have just been building off the same building blocks of earlier classes and modifying them slightly to create new antibiotics. Examining the extracts of plants used by traditional healers for infections may open up discovery of new chemical scaffolds for drug design, and provide important pathways for battling antibiotic-resistance.”

Related:

Chestnut leaves yield extract that disarms deadly bacteria

Tapping traditional remedies to fight modern super bugs

A future without antibiotics?

Tags:

Anthropology,

Biology,

Chemistry,

Ecology,

Health

Monday, February 6, 2017

Astronaut Mark Kelly to launch Atlanta Science Festival at Emory

Captain Mark Kelly, who led NASA missions into space, will lead off the action-packed schedule of this year's Atlanta Science Festival on Tuesday, March 14. His talk is entitled "Endeavor to Succeed." (NASA photo)

By Carol Clark

The 2017 Atlanta Science Festival blasts off on Tuesday, March 14 with a talk by Captain Mark Kelly – commander of Space Shuttle Endeavour’s final mission – at 7 pm in Emory’s Glenn Memorial Auditorium.

“We wanted to start off this year with someone who appeals to people of all ages and who epitomizes science in action,” says Meisa Salaita, co-executive director of the Atlanta Science Festival, which will continue through March 25 with events throughout the metro area. “Who better than an astronaut to show us how science can take us to new and exciting places?”

The title of Kelly’s talk is “Endeavour to Succeed.” Tickets for the event can be bought in advance on the Atlanta Science Festival’s web site for $12 ($8 for children 12 and under). They will also be available at the door the day of the event for $15.

Starting at 5:30 pm, during the countdown to Kelly’s talk, the public is invited to join toy rocket launching activities on the Glenn Memorial lawn, led by members of the Georgia Tech Ramblin’ Rocket Club and the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers.

Kelly, who began his NASA career in 1996, commanded the Space Shuttle Discovery, as well as the Endeavour. He left the astronaut corps in the summer of 2011 to help his wife, former U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, recover from gunshot wounds she received in an assassination attempt on her life. The couple’s story captivated the nation, and they went on to found Americans for Responsible Solutions to advocate for gun control.

NASA is comparing biological data from the Earth-bound Kelly with his identical twin brother, Scott Kelly, who recently spent a year in space. The unique Twins Study may offer insights into how to prepare astronauts for a long-term mission to Mars.

Kelly is also a prolific author, including numerous children’s books with space themes, and he will be available for a book signing following his talk at Emory.

The 12-day Atlanta Science Festival features talks, lab tours, film screenings, participatory activities and science demonstrations — more than 100 events at dozens of different venues, including the Emory campus. “We’ve expanded the number of days at the festival of the year, to avoid scheduling conflicts and give people a chance to experience more of the festival,” Salaita says. (Click here for the full schedule of events.)

Physics Live (at the Emory Mathematics and Science Center) and a Chemistry Carnival (at the Atwood Chemistry Center) will be among the Emory campus highlights, featuring lab tours and science demonstrations from 3:30 to 7 pm on Friday, March 24. (Click here for a full listing of Emory-related events.)

New at the festival this year will be an appearance by New York rap artist Baba Brinkman. He will perform “Rap Guide to Climate Chaos” at 1:30 on Saturday, March 18 at the Drew Charter School.

Also new this year is “The Art and Science of Cooking with Insects,” featuring free tastings, at 7:30 pm on Thursday, March 23 at Manuels Tavern.

About 20,000 visitors are expected for the festival’s culminating event, the Exploration Expo, from 11 am to 4 pm on Saturday, March 25 at Centennial Olympic Park. Around 100 interactive exhibits will delight curious minds of all ages, from Emory chemist’s Doug Mulford’s “Ping Pong Big Bang” to the immersive Google Village experience.

Leading sponsors of this year’s Atlanta Science Festival include Emory, Georgia Tech, the Metro Atlanta Chamber, Delta Airlines and Google.

By Carol Clark

The 2017 Atlanta Science Festival blasts off on Tuesday, March 14 with a talk by Captain Mark Kelly – commander of Space Shuttle Endeavour’s final mission – at 7 pm in Emory’s Glenn Memorial Auditorium.

“We wanted to start off this year with someone who appeals to people of all ages and who epitomizes science in action,” says Meisa Salaita, co-executive director of the Atlanta Science Festival, which will continue through March 25 with events throughout the metro area. “Who better than an astronaut to show us how science can take us to new and exciting places?”

The title of Kelly’s talk is “Endeavour to Succeed.” Tickets for the event can be bought in advance on the Atlanta Science Festival’s web site for $12 ($8 for children 12 and under). They will also be available at the door the day of the event for $15.

Starting at 5:30 pm, during the countdown to Kelly’s talk, the public is invited to join toy rocket launching activities on the Glenn Memorial lawn, led by members of the Georgia Tech Ramblin’ Rocket Club and the Institute of Electronic and Electrical Engineers.

Kelly, who began his NASA career in 1996, commanded the Space Shuttle Discovery, as well as the Endeavour. He left the astronaut corps in the summer of 2011 to help his wife, former U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, recover from gunshot wounds she received in an assassination attempt on her life. The couple’s story captivated the nation, and they went on to found Americans for Responsible Solutions to advocate for gun control.

NASA is comparing biological data from the Earth-bound Kelly with his identical twin brother, Scott Kelly, who recently spent a year in space. The unique Twins Study may offer insights into how to prepare astronauts for a long-term mission to Mars.

Kelly is also a prolific author, including numerous children’s books with space themes, and he will be available for a book signing following his talk at Emory.

The 12-day Atlanta Science Festival features talks, lab tours, film screenings, participatory activities and science demonstrations — more than 100 events at dozens of different venues, including the Emory campus. “We’ve expanded the number of days at the festival of the year, to avoid scheduling conflicts and give people a chance to experience more of the festival,” Salaita says. (Click here for the full schedule of events.)

Physics Live (at the Emory Mathematics and Science Center) and a Chemistry Carnival (at the Atwood Chemistry Center) will be among the Emory campus highlights, featuring lab tours and science demonstrations from 3:30 to 7 pm on Friday, March 24. (Click here for a full listing of Emory-related events.)

New at the festival this year will be an appearance by New York rap artist Baba Brinkman. He will perform “Rap Guide to Climate Chaos” at 1:30 on Saturday, March 18 at the Drew Charter School.

Also new this year is “The Art and Science of Cooking with Insects,” featuring free tastings, at 7:30 pm on Thursday, March 23 at Manuels Tavern.

About 20,000 visitors are expected for the festival’s culminating event, the Exploration Expo, from 11 am to 4 pm on Saturday, March 25 at Centennial Olympic Park. Around 100 interactive exhibits will delight curious minds of all ages, from Emory chemist’s Doug Mulford’s “Ping Pong Big Bang” to the immersive Google Village experience.

Leading sponsors of this year’s Atlanta Science Festival include Emory, Georgia Tech, the Metro Atlanta Chamber, Delta Airlines and Google.

Thursday, February 2, 2017

If you dig survival, read 'The Evolution Underground'

"Some animals were born to run. Others were born to burrow," says Emory paleontologist Anthony Martin, shown with the cast of a crustacean burrow from the Georgia coast. (Photo by Lisa Streib.)

By Carol Clark

The dirt flies in Emory paleontologist Anthony Martin’s new tell-all book, “The Evolution Underground: Burrows, Bunkers and the Marvelous Subterranean World Beneath Our Feet.” The book takes readers on a head-spinning tour of the underworld, from the tiny tunnels drilled by modern-day earthworms to the massive, four-meter-wide paleo-burrows excavated by the Pleistocene’s giant sloths.

“I want people to understand how the evolution of burrowing has shaped the environments we see today, from the ocean floor to high mountaintops,” Martin says. “Burrowing strategies are also key to the survival of many species – beyond just the burrowers themselves.”

Martin is a leading expert of ichnology – the study of trace fossils, including burrows, nests, tracks and feces. “The Evolution Underground,” published by Pegasus Books, is Martin’s seventh book, and his second aimed at a general audience, after 2014’s “Dinosaurs Without Bones.”

In the following interview, he reveals some of nature’s deepest, darkest secrets.

Q. When did burrowing behaviors begin in animals?

Tony Martin: The earliest evidence we have for burrowing goes back 550 million years, with marine animals. But these early burrowers, including trilobites, didn’t go very deep. If you think of the sea floor like a carpet, they were digging into the top of it or just beneath it, probably mining the sediment for food.

Around 545 million years ago, trilobites, marine worms and other invertebrates starting going deeper, burrowing vertically. They were probably both seeking organic particles for food and shelter against predators. Soon after that, predators started burrowing and the arms race was on.

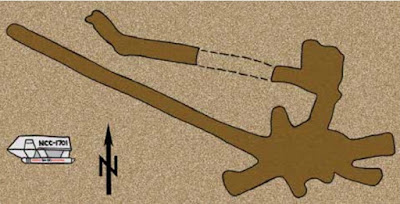

Map of tunnel system made by Pleistocene giant ground sloths. U.S.S. Enterprise shuttlecraft (7 meters/23 feet long) for scale. (Figure by Anthony Martin.)

Q. How did these burrowers impact the environment?

TM: By punching down into the seabed, they put oxygen down into sediment that normally wasn’t exposed to it. That started oxidizing elements on the ocean floor, changing the carbon, phosphorous, nitrogen and sulphur cycles. So burrowing changed the ocean chemistry, which in turn had an influence on atmospheric chemistry. These early burrowers were ecosystem engineers.

They were also highly adaptable. The invasion of land by ocean life may have been facilitated by burrowing, enabling some species to make the transition to a new environment.

Q. So burrowers were the original survivalists?

TM: Yes! Burrowing enabled animals to make it through the worst that Earth threw at them – or even the worst that the solar system threw at them. A lot of animals, for example, lived after a large asteroid impact killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Why did they survive? They were in their bunkers! It’s likely there were other factors, but burrowing is definitely an advantage when you get a giant space rock dropped on you.

There are modern examples, as well. After the 1980 eruption by Mount St. Helens, scientists flew over this barren, smoldering wasteland in helicopters. All the largest animals were gone. One of the only signs of life was the tops of pocket gopher burrows. Ecologists determined that pocket gophers didn’t just survive the explosion, they helped the entire ecosystem come back. They mined the soil and brought up seeds from below, restoring vegetation. And their burrows provided microhabitats for reptiles and amphibians in the area.

Pocket gophers aren’t the only ecological heroes. Gopher tortoises dig burrows six-meters deep and create an underground zoo of diversity. Some 300-to-400 species live alongside the tortoises in their burrows, including indigo snakes, the longest snake native to North America, and rattlesnakes.

Behold an ecological hero — the pocket gopher! (Photo by Ty Smedes, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.)

Q. Do any animals stand out as the best burrowers?

TM: It depends on how you define “best,” but when it comes to the amount of soil overturned, ants are the rulers of the underground. Leafcutter ants create these spiral, vertical shafts that go down two meters and branch into a labyrinth of tunnels that connect to outer chambers. A recent excavation of a leafcutter colony in Brazil showed that these tiny insects had to move about 40 tons of soil to create their underground city. That’s the ant equivalent of the Great Wall of China, in terms of the effort that went into it. And that’s just a single ant colony. Especially compared to their size, ants have a disproportionate impact on ecosystems.

Q. What about human burrowing behaviors?

TM: Humans also burrow to survive predation and environmental extremes. The massive underground cities carved out of volcanic ash in Cappadocia, Turkey, during Byzantine times served as safe havens during times of war. Fears of nuclear warfare during the Cold War prompted the U.S. military to build networks of underground bunkers.

Montreal’s The Underground City was created mainly to deal with Canada’s long winters. People live, shop and go to the office while staying in a climate-controlled environment. And in the opal-mining town of Coober Pedy, in the Outback of Australia, people have adapted to the scorching heat by building underground houses.

We can learn a lot from burrowers of the geologic past, as well as the burrowing animals of today. If you want to survive a mass extinction, for example, you should probably start digging.

Related:

Bringing to life 'Dinosaurs Without Bones'

Dinosaur burrows yield clues to climate change

Lake bed trails tell ancient fish story

By Carol Clark

The dirt flies in Emory paleontologist Anthony Martin’s new tell-all book, “The Evolution Underground: Burrows, Bunkers and the Marvelous Subterranean World Beneath Our Feet.” The book takes readers on a head-spinning tour of the underworld, from the tiny tunnels drilled by modern-day earthworms to the massive, four-meter-wide paleo-burrows excavated by the Pleistocene’s giant sloths.

“I want people to understand how the evolution of burrowing has shaped the environments we see today, from the ocean floor to high mountaintops,” Martin says. “Burrowing strategies are also key to the survival of many species – beyond just the burrowers themselves.”

Martin is a leading expert of ichnology – the study of trace fossils, including burrows, nests, tracks and feces. “The Evolution Underground,” published by Pegasus Books, is Martin’s seventh book, and his second aimed at a general audience, after 2014’s “Dinosaurs Without Bones.”

In the following interview, he reveals some of nature’s deepest, darkest secrets.

Q. When did burrowing behaviors begin in animals?

Tony Martin: The earliest evidence we have for burrowing goes back 550 million years, with marine animals. But these early burrowers, including trilobites, didn’t go very deep. If you think of the sea floor like a carpet, they were digging into the top of it or just beneath it, probably mining the sediment for food.

Around 545 million years ago, trilobites, marine worms and other invertebrates starting going deeper, burrowing vertically. They were probably both seeking organic particles for food and shelter against predators. Soon after that, predators started burrowing and the arms race was on.

Map of tunnel system made by Pleistocene giant ground sloths. U.S.S. Enterprise shuttlecraft (7 meters/23 feet long) for scale. (Figure by Anthony Martin.)

Q. How did these burrowers impact the environment?

TM: By punching down into the seabed, they put oxygen down into sediment that normally wasn’t exposed to it. That started oxidizing elements on the ocean floor, changing the carbon, phosphorous, nitrogen and sulphur cycles. So burrowing changed the ocean chemistry, which in turn had an influence on atmospheric chemistry. These early burrowers were ecosystem engineers.

They were also highly adaptable. The invasion of land by ocean life may have been facilitated by burrowing, enabling some species to make the transition to a new environment.

Q. So burrowers were the original survivalists?

TM: Yes! Burrowing enabled animals to make it through the worst that Earth threw at them – or even the worst that the solar system threw at them. A lot of animals, for example, lived after a large asteroid impact killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Why did they survive? They were in their bunkers! It’s likely there were other factors, but burrowing is definitely an advantage when you get a giant space rock dropped on you.

There are modern examples, as well. After the 1980 eruption by Mount St. Helens, scientists flew over this barren, smoldering wasteland in helicopters. All the largest animals were gone. One of the only signs of life was the tops of pocket gopher burrows. Ecologists determined that pocket gophers didn’t just survive the explosion, they helped the entire ecosystem come back. They mined the soil and brought up seeds from below, restoring vegetation. And their burrows provided microhabitats for reptiles and amphibians in the area.

Pocket gophers aren’t the only ecological heroes. Gopher tortoises dig burrows six-meters deep and create an underground zoo of diversity. Some 300-to-400 species live alongside the tortoises in their burrows, including indigo snakes, the longest snake native to North America, and rattlesnakes.

Behold an ecological hero — the pocket gopher! (Photo by Ty Smedes, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.)

Q. Do any animals stand out as the best burrowers?

TM: It depends on how you define “best,” but when it comes to the amount of soil overturned, ants are the rulers of the underground. Leafcutter ants create these spiral, vertical shafts that go down two meters and branch into a labyrinth of tunnels that connect to outer chambers. A recent excavation of a leafcutter colony in Brazil showed that these tiny insects had to move about 40 tons of soil to create their underground city. That’s the ant equivalent of the Great Wall of China, in terms of the effort that went into it. And that’s just a single ant colony. Especially compared to their size, ants have a disproportionate impact on ecosystems.

Q. What about human burrowing behaviors?

TM: Humans also burrow to survive predation and environmental extremes. The massive underground cities carved out of volcanic ash in Cappadocia, Turkey, during Byzantine times served as safe havens during times of war. Fears of nuclear warfare during the Cold War prompted the U.S. military to build networks of underground bunkers.

Montreal’s The Underground City was created mainly to deal with Canada’s long winters. People live, shop and go to the office while staying in a climate-controlled environment. And in the opal-mining town of Coober Pedy, in the Outback of Australia, people have adapted to the scorching heat by building underground houses.

We can learn a lot from burrowers of the geologic past, as well as the burrowing animals of today. If you want to survive a mass extinction, for example, you should probably start digging.

Related:

Bringing to life 'Dinosaurs Without Bones'

Dinosaur burrows yield clues to climate change

Lake bed trails tell ancient fish story

Tags:

Biology,

Chemistry,

Climate change,

Ecology

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)