Wednesday, May 29, 2013

A healthy business is in his cards

Eddie Kovel just graduated from Emory with the unusual combination of a business major and a predictive health minor, fashioned with the support of the Center for the Study of Human Health. One of the fastest growing sectors in the economy, the human health field is creating new opportunities in medicine, business, law, public policy, the arts and elsewhere.

“There’s definitely an emerging need for business-minded health professionals and health-minded business professionals,” Kovel says.

Kovel has developed a card game called “Playout” which aims to motivate people to exercise. He’s now working to spread the word about the product, and its philosophy of having fun while getting fit.

Related:

Predictive health: A call to reinvent medicine

Friday, May 24, 2013

A medical exhibit that won't put you to sleep

"Medical Treasures at Emory" is an exhibit of historical artifacts that serve as reminders of the days when doctors had a rudimentary understanding of human anatomy, performed surgery without antiseptic and used primitive forms of anesthesia for operations and dental work.

The above video gives a peek at some of the objects on display through October at the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library. Notable artifacts include one of the earliest stethoscopes from the 19th century, and a kit of Civil War surgeon's instruments, primarily used for amputation.

Among the historical books on display are volumes about Civil War field surgery practices, an 1881 book that incorporates early medical photography to show the ravages of syphilis, a copy of "Notes on Nursing: What It is, and What It Is Not" (1865) by Florence Nightingale, and an 1849 obstetrics book by Charles D. Meigs, an obstetrician who opposed anesthesia and the introduction of sanitary practices during childbirth on the theory that "doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman's hands are clean."

Also on display is a rare copy of "One the Workings of the Human Body," or "de Humani corporis fabrica," a 1543 book containing the first accurate representations of human anatomy.

Read more about the exhibit.

Related:

The rare book that changed medicine

Objects of our afflictions

The above video gives a peek at some of the objects on display through October at the Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library. Notable artifacts include one of the earliest stethoscopes from the 19th century, and a kit of Civil War surgeon's instruments, primarily used for amputation.

Among the historical books on display are volumes about Civil War field surgery practices, an 1881 book that incorporates early medical photography to show the ravages of syphilis, a copy of "Notes on Nursing: What It is, and What It Is Not" (1865) by Florence Nightingale, and an 1849 obstetrics book by Charles D. Meigs, an obstetrician who opposed anesthesia and the introduction of sanitary practices during childbirth on the theory that "doctors are gentlemen and a gentleman's hands are clean."

Also on display is a rare copy of "One the Workings of the Human Body," or "de Humani corporis fabrica," a 1543 book containing the first accurate representations of human anatomy.

Read more about the exhibit.

Related:

The rare book that changed medicine

Objects of our afflictions

Monday, May 20, 2013

Parasitic wasps use calcium pump to block fruit-fly immunity

A parasitic wasp on the prowl for fruit fly larva to inject with her eggs.

By Carol Clark

Parasitic wasps switch off the immune systems of fruit flies by draining calcium from the flies’ blood cells, a finding that offers new insight into how pathogens break through a host’s defenses.

“We believe that we have discovered an important component of cellular immunity, one that parasites have learned to take advantage of,” says Emory University biologist Todd Schlenke, whose lab led the research.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the results, showing how a wasp version of a conserved protein called SERCA, which normally functions to pump calcium from the cell cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum, can block a host’s cellular immune response.

“Before our study, there were hints that calcium signaling was important for blood cell activation following infection, but the fact that a parasite actively suppresses this signaling shows how important it is, Schlenke says. He adds that the insects can serve as a model for more complex human immune systems.

“It’s incredible the way the wasps use a protein in their venom to control the flies at a molecular level,” says Nathan Mortimer, a post-doctoral fellow in the Schlenke lab who conducted the experiments. “Instead of killing the fly immune cells, the wasps actually take over blood-cell signaling, manipulating the host’s cellular behavior from the bottom up.”

The research team also included Emory biologist Balint Kacsoh; Jeremy Goecks and James Taylor, from Emory’s departments of biology and mathematics and computer science; and James Mobley and Gregory Bowersock of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

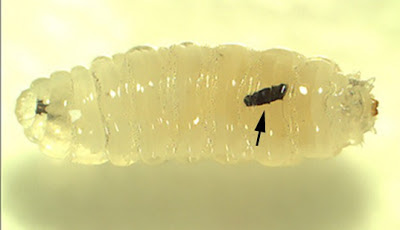

Fruit fly wins: A wasp egg has turned black and died (see arrow) inside the larva of a fruit fly that has mounted a successful immune response.

Fruit flies and the tiny wasps that parasitize them have co-evolved complex strategies of attack and defense. The wasps inject their eggs into the body cavities of fruit fly larvae, along with venom that aims to suppress the flies’ cellular immunity. If the flies fail to kill the wasp egg, a wasp larva hatches inside the fruit fly larva and begins to eat its host from the inside out.

“The wasp larvae have these sharp appendages, like the fingers of Edward Scissorhands, that they use to stick into the fly tissue and start eating,” Mortimer says. “It’s a brutal process.”

In previous research, the Schlenke lab has shown how fruit flies sometimes use alcohol in rotting fruit as a drug to kill the wasps.

In the current study, the researchers focused on the molecular attack strategies of the wasps. After sequencing the transcriptome of the newly described wasp species Ganaspis sp.1, they took a proteomic approach to identify peptide sequences out of the wasp’s venom gland, which they could then link back to full-length transcript sequences.

“We found that the venom of Ganaspis sp.1 is a toxic cocktail of 170 different proteins,” Schlenke says, “but the most prominent component was the SERCA calcium pump protein. That really surprised us.”

Wasps win: Arrows point to wasp larvae that have successfully blocked the fruit-fly immune response and are eating the tissue of the fruit fly.

Calcium pumps are found in the membranes of every living cell of every animal, and are needed to maintain ionic homeostasis and cellular stability. One type of pump moves calcium ions out of the endoplasmic reticulum and into the cytoplasm where they transmit signals that activate other proteins. The SERCA calcium pump operates in the opposite direction, sucking calcium ions out of the cytoplasm and back into storage.

“We wondered why the wasps would inject the flies with a protein that the flies already have, and that every cell needs to function,” Schlenke says. “How could that be an infection strategy?”

The researchers knew of studies suggesting that a calcium burst in cytoplasm is associated with the activation of human blood cells. They wondered if something similar was happening with the flies.

Mortimer conducted experiments on a transgenic fly strain with cells that fluoresce in the presence of calcium. He found that the fly blood cells release a burst of calcium into their cytoplasm, and that this activates the blood cells to start homing in on the wasp eggs. Genetically increasing or decreasing blood-cell calcium levels makes the flies more or less resistant to the parasite infection.

“The wasp venom prevents this calcium burst, and it’s like the fly blood cells don’t realize they’re supposed to be responding to infection,” Mortimer says. “The venom essentially sucks the calcium out of the fly’s blood cells.”

The experiments showed that the wasp venom is specifically targeted to the fly blood cells, and has no effect on other cells.

An unresolved question is how a SERCA protein, which is hydrophobic and normally resides in an oily membrane, moves out of a wasp venom cell and makes its way into a fly blood cell.

“We have no idea how it works,” Schlenke says, “but somehow this calcium pump moves through all these environments and finds its way into its target cells.”

The researchers hypothesize that virus-like particles in the wasp’s venom may be involved. “If they aren’t really viruses, they seem to be some virus-like thing that the wasp has invented,” Schlenke says. “It’s pure speculation, but we think maybe the wasps use these particles as delivery vehicles for the calcium pumps.”

Previous research has established that fruit fly immune signaling pathways have homologues in humans, making fruit flies a valuable model for learning about human immunity. That work led to the award of the 2011 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine to Jules Hoffmann, a fruit fly immunologist.

Studying the wasp-fly battle for survival at the molecular level provides a powerful new tool for unlocking more secrets of immunity that could apply to human health, Mortimer says.

“I’m also interested in using the flies to understand more about the immune systems of mosquitos and other insect vectors of human disease,” he says. “If we could somehow boost vector insect immunity, it could decrease transmission of human disease like malaria.”

Related:

Fruit flies use alcohol as a drug to kill parasites

Fruit flies force their young to drink alcohol -- for their own good

What aphids can teach us about immunity

By Carol Clark

Parasitic wasps switch off the immune systems of fruit flies by draining calcium from the flies’ blood cells, a finding that offers new insight into how pathogens break through a host’s defenses.

“We believe that we have discovered an important component of cellular immunity, one that parasites have learned to take advantage of,” says Emory University biologist Todd Schlenke, whose lab led the research.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the results, showing how a wasp version of a conserved protein called SERCA, which normally functions to pump calcium from the cell cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum, can block a host’s cellular immune response.

“Before our study, there were hints that calcium signaling was important for blood cell activation following infection, but the fact that a parasite actively suppresses this signaling shows how important it is, Schlenke says. He adds that the insects can serve as a model for more complex human immune systems.

“It’s incredible the way the wasps use a protein in their venom to control the flies at a molecular level,” says Nathan Mortimer, a post-doctoral fellow in the Schlenke lab who conducted the experiments. “Instead of killing the fly immune cells, the wasps actually take over blood-cell signaling, manipulating the host’s cellular behavior from the bottom up.”

The research team also included Emory biologist Balint Kacsoh; Jeremy Goecks and James Taylor, from Emory’s departments of biology and mathematics and computer science; and James Mobley and Gregory Bowersock of the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Fruit flies and the tiny wasps that parasitize them have co-evolved complex strategies of attack and defense. The wasps inject their eggs into the body cavities of fruit fly larvae, along with venom that aims to suppress the flies’ cellular immunity. If the flies fail to kill the wasp egg, a wasp larva hatches inside the fruit fly larva and begins to eat its host from the inside out.

“The wasp larvae have these sharp appendages, like the fingers of Edward Scissorhands, that they use to stick into the fly tissue and start eating,” Mortimer says. “It’s a brutal process.”

In previous research, the Schlenke lab has shown how fruit flies sometimes use alcohol in rotting fruit as a drug to kill the wasps.

In the current study, the researchers focused on the molecular attack strategies of the wasps. After sequencing the transcriptome of the newly described wasp species Ganaspis sp.1, they took a proteomic approach to identify peptide sequences out of the wasp’s venom gland, which they could then link back to full-length transcript sequences.

“We found that the venom of Ganaspis sp.1 is a toxic cocktail of 170 different proteins,” Schlenke says, “but the most prominent component was the SERCA calcium pump protein. That really surprised us.”

Wasps win: Arrows point to wasp larvae that have successfully blocked the fruit-fly immune response and are eating the tissue of the fruit fly.

Calcium pumps are found in the membranes of every living cell of every animal, and are needed to maintain ionic homeostasis and cellular stability. One type of pump moves calcium ions out of the endoplasmic reticulum and into the cytoplasm where they transmit signals that activate other proteins. The SERCA calcium pump operates in the opposite direction, sucking calcium ions out of the cytoplasm and back into storage.

“We wondered why the wasps would inject the flies with a protein that the flies already have, and that every cell needs to function,” Schlenke says. “How could that be an infection strategy?”

The researchers knew of studies suggesting that a calcium burst in cytoplasm is associated with the activation of human blood cells. They wondered if something similar was happening with the flies.

Mortimer conducted experiments on a transgenic fly strain with cells that fluoresce in the presence of calcium. He found that the fly blood cells release a burst of calcium into their cytoplasm, and that this activates the blood cells to start homing in on the wasp eggs. Genetically increasing or decreasing blood-cell calcium levels makes the flies more or less resistant to the parasite infection.

“The wasp venom prevents this calcium burst, and it’s like the fly blood cells don’t realize they’re supposed to be responding to infection,” Mortimer says. “The venom essentially sucks the calcium out of the fly’s blood cells.”

The experiments showed that the wasp venom is specifically targeted to the fly blood cells, and has no effect on other cells.

An unresolved question is how a SERCA protein, which is hydrophobic and normally resides in an oily membrane, moves out of a wasp venom cell and makes its way into a fly blood cell.

“We have no idea how it works,” Schlenke says, “but somehow this calcium pump moves through all these environments and finds its way into its target cells.”

The researchers hypothesize that virus-like particles in the wasp’s venom may be involved. “If they aren’t really viruses, they seem to be some virus-like thing that the wasp has invented,” Schlenke says. “It’s pure speculation, but we think maybe the wasps use these particles as delivery vehicles for the calcium pumps.”

Previous research has established that fruit fly immune signaling pathways have homologues in humans, making fruit flies a valuable model for learning about human immunity. That work led to the award of the 2011 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine to Jules Hoffmann, a fruit fly immunologist.

Studying the wasp-fly battle for survival at the molecular level provides a powerful new tool for unlocking more secrets of immunity that could apply to human health, Mortimer says.

“I’m also interested in using the flies to understand more about the immune systems of mosquitos and other insect vectors of human disease,” he says. “If we could somehow boost vector insect immunity, it could decrease transmission of human disease like malaria.”

Related:

Fruit flies use alcohol as a drug to kill parasites

Fruit flies force their young to drink alcohol -- for their own good

What aphids can teach us about immunity

Tags:

Biology,

Chemistry,

Ecology,

Environmental Studies,

Health

Friday, May 17, 2013

Star Trek and the ethics of space exploration

Who owns the moon? Is it fair to send people on a one-way trip to Mars? Can doctors safeguard medical experiments in other environments? These are just a few of the ethical questions confronting the human race as we continue to explore space.

The Emory Looks at Hollywood series examines these questions in context of the new Paramount Pictures movie "Star Trek Into Darkness," the latest in the long-running Star Trek story. Watch the video above as Paul Root Wolpe, Director of the Center for Ethics at Emory and the first Senior Bioethicist for NASA, discusses the ethics of space exploration.

Related: Scientist tackles the ethics of space travel

Tags:

Bioethics,

Health,

Physics,

Science and Art/Media

Thursday, May 16, 2013

Think you can win Powerball? Don't bet on it

The Powerball jackpot is up to $475 million, the second-largest in the lottery's history. Lottery officials put the odds of winning at one in 195 million, "meaning you are 251 times more likely to be hit by lightning," reports Alan Farnham of ABC's Good Morning America.

Below is an excerpt from Farnham's report:

"Skip Garibaldi, a professor of mathematics at Emory University in Atlanta, provides additional perspective: You are more likely to die from all of the following than you are to win tonight's drawing: be hit by a falling coconut, be blown up by fireworks, or be eaten by flesh-eating bacteria.

"Even though he knows the odds all too well, Garibaldi says that he has played past lotteries. 'When it gets big, I'll buy a couple of tickets. It's kind of exciting. You get this feeling of anticipation. You get to think about the fantasy.'

"Writing for the New York Post, Garibaldi recently reviewed the book 'Brain Trust,' in which 93 scientists give advice on subjects that include how to win the lottery.

"Their advice, he says, includes the following:

"Pick the most unpopular numbers. Avoid, for example, numbers thought to be 'lucky,' such as 7, 13, 23 and 32.

"Don't pick the number 1. It's on about 15 percent of all tickets.

"Do pick the 'especially overlooked' number 46.

"Garibaldi's own advice: Look for a jackpot that's rolled over at least five times yet still remains below $40 million. And be sure not to overlook state lotteries, which have fewer people competing for their pots."

Read the full report on the GMA website.

Related:

Lottery study zeros in on risk

Below is an excerpt from Farnham's report:

"Skip Garibaldi, a professor of mathematics at Emory University in Atlanta, provides additional perspective: You are more likely to die from all of the following than you are to win tonight's drawing: be hit by a falling coconut, be blown up by fireworks, or be eaten by flesh-eating bacteria.

"Even though he knows the odds all too well, Garibaldi says that he has played past lotteries. 'When it gets big, I'll buy a couple of tickets. It's kind of exciting. You get this feeling of anticipation. You get to think about the fantasy.'

"Writing for the New York Post, Garibaldi recently reviewed the book 'Brain Trust,' in which 93 scientists give advice on subjects that include how to win the lottery.

"Their advice, he says, includes the following:

"Pick the most unpopular numbers. Avoid, for example, numbers thought to be 'lucky,' such as 7, 13, 23 and 32.

"Don't pick the number 1. It's on about 15 percent of all tickets.

"Do pick the 'especially overlooked' number 46.

"Garibaldi's own advice: Look for a jackpot that's rolled over at least five times yet still remains below $40 million. And be sure not to overlook state lotteries, which have fewer people competing for their pots."

Read the full report on the GMA website.

Related:

Lottery study zeros in on risk

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)