Women in Upper Jidao village, Guizhou, wear their festival attire and perform Miao songs and dances for tourists. Photo by Jenny Chio.

By Carol Clark

While most of the world has been dazzled by the transformation of China’s cities in recent years, Emory anthropologist Jenny Chio has been quietly recording changes in the rural way of life. Her documentary film “农家乐 Peasant Family Happiness” explores the impact of tourism in China, from the perspective of residents of two rural villages where urbanites go to seek a “country” experience.

“I’m fascinated by tourism and I think it’s an important topic,” Chio says, “but I don’t study tourists. I made a decision early on to focus instead on the people who are actually doing the work to create an enjoyable, cultural experience for the tourists.”

Watch a BBC interview with Jenny Chio:

Chio was born in the United States, to parents who immigrated from Taiwan in the early 1970s. She was raised in the Midwest and California and speaks Mandarin Chinese.

As an undergraduate majoring in anthropology at Brown University she became interested in museums, particularly those run by Native Americans, and how they are used to address historical trauma and promote revitalization of cultural heritage.

After graduation, she spent a year teaching English in Beijing. “That’s when I realized that everything that I thought I knew about China was inadequate,” Chio says. “It was like, ‘Wow! I have so much to learn about this place.’”

The crowds of people, cars and non-stop construction can feel overwhelming to a first-time visitor to a city in China, she says. “Beijing is much louder than an American city. There is this energy that comes from the fact that life in China has changed so dramatically, so quickly. The buildings are so new and so shiny and modern.”

She cites a running joke: Reports of Chinese tourists going to Europe and the United States and being disappointed that the cities look so old and decrepit in comparison.

Chio went to Goldsmiths College, University of London, for a masters degree in visual anthropology. For her thesis, she created a digital video on the representation of ethnic minorities in Chinese ethnographic films from the 1950s and 1960s, titled “Film the People.”

In this still image from "Peasant Family Happiness" a village woman muses whether she should maintain an "ethnic" look while doing her household chores.

While “visual anthropology” is fairly new as a term and as a sub-discipline, “anthropologists have been using still photos and film cameras since their invention,” Chio says. “But many in the field have considered imagery as too slippery for communicating research because you can’t control how people interpret it. My take is that images are obviously important, but they have to be used very consciously, with an awareness of what they can and cannot do. Film speaks to us in one way and text in another. I’m interested in how they may work together.”

Chio began filming the villages in “农家乐 Peasant Family Happiness” in 2006 as part of her thesis for a PhD in socio-cultural anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley.

Domestic tourism is booming in China. As the middle class has blossomed in cities, the government has promoted tourism in the countryside, to help address the vast economic disparities between the urban and rural populations. The term “peasant family happiness,” or nong jia le, became a catch-all phrase to describe the phenomenon of homestays and guesthouses where “city slickers” can unwind while enjoying local food and activities.

A villager at work in a rice field. Photo by Jenny Chio.

Here’s an excerpt of a review of Chio's documentary, published by the journal American Anthropologist:

“The film opens with some striking footage of tourists being carried up steep slopes in colorful canopied bamboo sedan chairs. Ping’an men keep tallies on whose turn it is to carry the next passenger at the sedan chair boarding station. From an observation point, a tour guide in ethnic dress armed with a microphone rallies the tour group, consisting of urban Chinese tourists, to admire the rural landscape.”

“It’s fascinating to me all the types of labor involved in creating and maintaining tourism in these villages,” Chio says. “The visitors must be fed and entertained. And the villagers have to learn how to re-visualize their living spaces and environments. Jeans and t-shirts, for example, may be cheaper, but the tourists expect to see villagers in ethnic dress.”

The tourists may want to have a cultural experience, but they don’t necessarily want it to include strong smells. In order to create a guesthouse, village families must consider whether they need to move their pigs away from their traditional location, beneath homes, to pens further away.

A flush toilet and indoor plumbing, uncommon luxuries in many villages, are basic essentials for city folk. Windows may need to be screened, and a balcony added to a room to make it more desirable. A concrete house may be more practical, and less of a fire hazard, but a wooden home is more picturesque.

One of Chio’s favorite scenes from the film shows about two dozen men from Ping’an strapping a 2,000-kilogram electrical transformer to two tree trunks, then hefting the trunks to their shoulders and carrying the transformer up a steep slope. “I don’t actually explain what’s going on to the viewers,” Chio says, “but, of course, if you’re going to bring more electrical capacity to an 800-meter-high village with only footpaths and one narrow road, then you are going to have to pack in a larger transformer. When the men finally arrive at the place where they can set it down, you hear this collective groan and cheer that sounds so tired and full of relief. It was a pretty amazing, joyous moment for the village.”

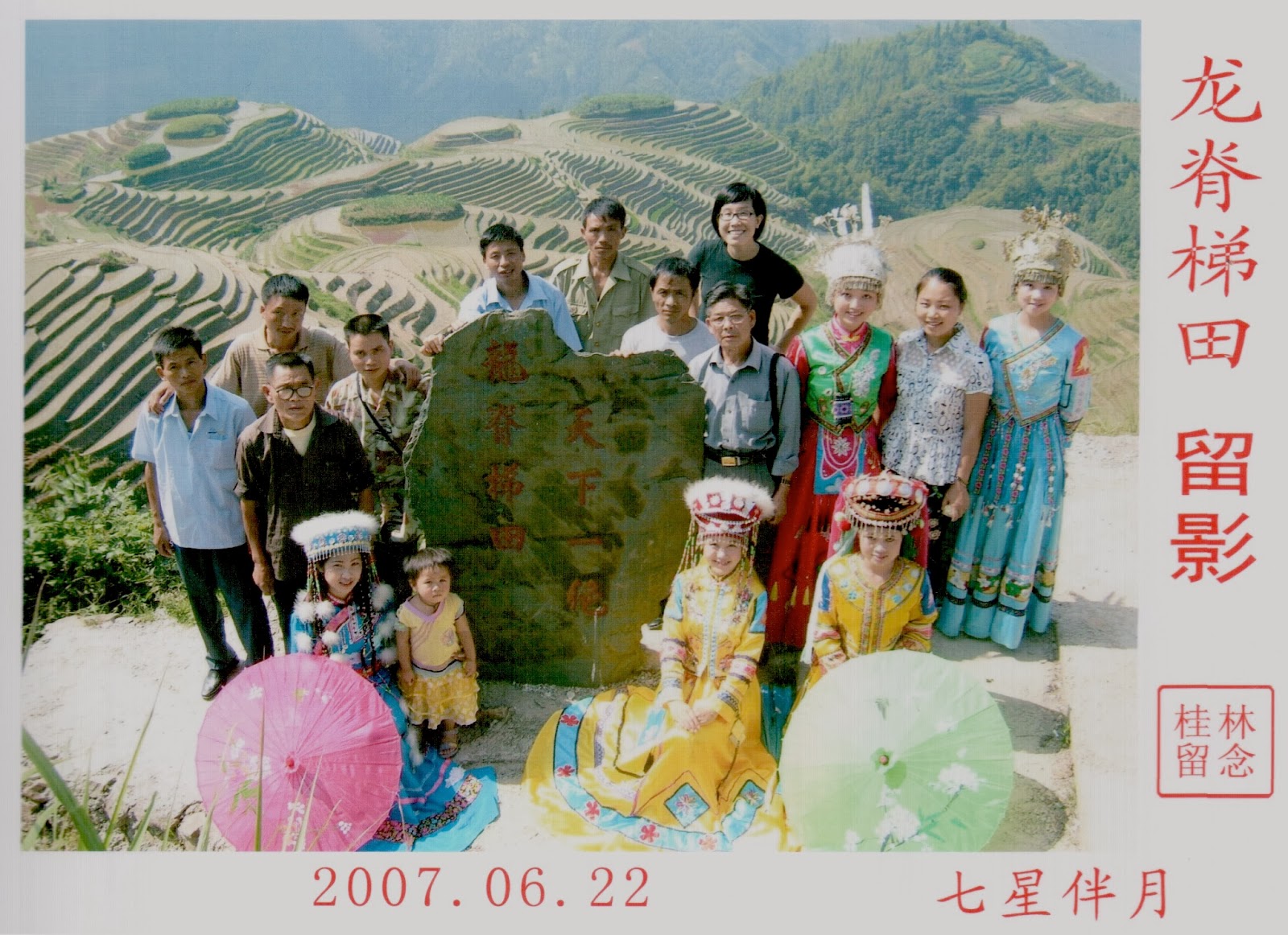

Residents of Upper Jidao and Jenny Chio pose with "minority models" for a souvenir photograph in Ping'an.

As more village youth graduate from college, rural tourism gives them an opportunity to return and run a hotel or other business. “They may help their parents create web sites for a guesthouse and build networks with travel companies,” Chio says.

Among the negative effects of tourism are environmental problems. “Tourism uses a lot of resources, like water and energy,” Chio notes. “It also makes village residents much more aware of the inequities between rural and urban parts of the country.”

China’s population recently tipped for the first time into a predominantly semi-urban-to-urban one, but 49 percent of the country remains rural.

“Rural China sits at the heart of a lot of key issues that the government has to deal with,” Chio says, including political instability at the local level, the critical need for food security, population mobility and tensions between the “haves” and “have nots.” The rapid urbanization of China has put more pressure on the government to help the countryside catch up.

Chio’s next project is focused on the digital technology and media practices of rural China. In some areas, non-governmental agencies have been training villagers in video production. The videos appear to have varying aims, from fostering awareness of social issues and environmental problems to simply offering glimpses of local festivals and other events.

“Making short, home-movie-style videos of local ethnic life is becoming a part of everyday life in rural China,” Chio says. “People are selling some of these videos at street stalls and in shops. I want to learn more about what these videos portray, who is making them, and who is buying them.”

No comments:

Post a Comment